by The Cowl Editor on December 8, 2017

Christmas

by Madison Stevens ’19

There is blood everywhere. That’s all I am aware of at this point—wet, metallic-smelling blood. On the operating room floor, on gauze packs, on me. I survived my twelfth day at Saint Mary’s Hospital in Austin. A Christmas miracle, to say the least. I had done my first year residency in Dallas but moved to train under the best after I decided on my specialty in cardiothoracic surgery. As the harsh florescent lights of the O.R. stare me in the face, I am very much regretting my decision.

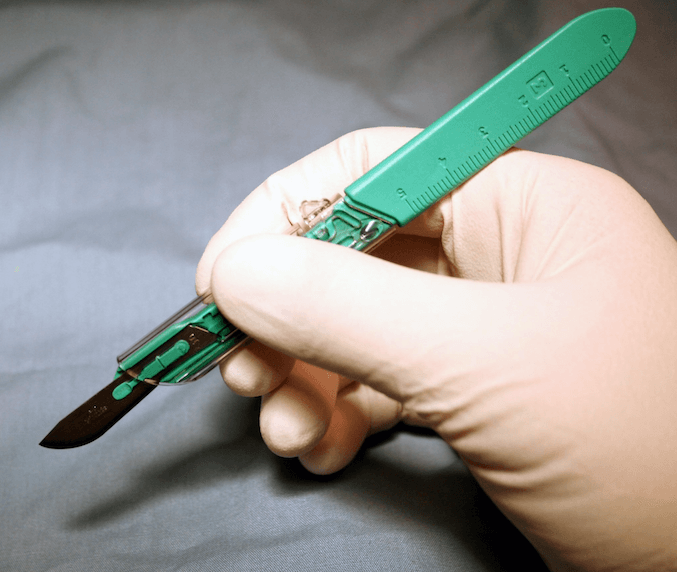

I live for the rush of the hospital, for the unsanitary in the midst of complete sterilization. Blood hitting the bleached floors of the O.R., a completely diseased organ in the safety of my latex glove-covered hand, a placenta sliding into a medical waste bag as a mother swaddles her newborn baby girl. I live for it. The hospital welcomes life and strives to delay death. I live for the first cut, taking the scalpel and initiating my workspace with a drag of the blade across an abdomen, chest, leg, or scalp. These are the things that surgeons think about, I think to myself so I don’t feel as crazy as I tie the waistband on my scrubs. I retrieve three charts from the nurses’ station, all post-ops, and look it over. “December 25” is displayed on the sticky calendar on the desk. It couldn’t be more perfect that today was Christmas, for today I am getting the best possible gift I can imagine: the meat and potatoes of surgery specialties—working in the cardiothoracic wing under Dr. Gerald Hallen.

“Dr. Penelope Kannery?” I hear my name in a deep voice from behind me. I turn around and look up; my 5’9 frame suddenly feels tiny in the presence of Dr. Hallen. He has to be mid- to late-40s, though there are no traces of laugh lines around his eyes; just frown lines framing his chin.

“Yes Dr. Hallen, that’s me. I was on my way down to the cardio wing.” I say with a smile. His face remains neutral.

“You’re here earlier than your call. That’s good. Follow me and keep up.” And he’s off down the hall. I hear two nurses mumble “the Grinch” under their breath as we pass by. He comes to an abrupt stop in front of a room, turns around, and shoves a binder with all of the patient information at my waist, saying, “30 seconds to review. Do not speak to the patient.”

Yeah, he’s the Grinch all right. Okay, Henry Sidler, 72, he needs a coronary artery bypass graft surgery, the most common of heart surgeries—one that I studied endlessly in med school and scrubbed in on four times back in Dallas. I walk in behind him and wait as he explains to Henry what would happen during his surgery.

“And as I have said before, it is the most common heart surgery preformed, though that doesn’t mean things cannot go wrong. I have—” Dr. Hallen was beginning another sentence as Henry cut him off, causing the world-renowned doctor to have a look on his face as if somebody kicked his puppy.

“Yeah, yeah, Doc, you’ve told me all of this before, can I get back to my game of solitaire? My granddaughter gave me these cards for Christmas,” Henry says with a nervous laugh, gesturing at his playing cards displayed on the makeshift table on his lap.

“As. I. Was. Saying. I have an extremely high success rate, and there have only been good things said about Dr. Penelope Kannery, so we’ll see if that’s true,” Dr. Hallen finishes as poor Henry looks at him wearily. Grinch.

“You have nothing to worry about, Mr. Sidler. You are in the best hands possible, Dr. Hallen has done this surgery hundreds of times. Try not to worry, this is the best Christmas gift you could be receiving—after the cards of course,” I say with a smile and a squeeze to his arm. Dr. Hallen storms out of the room. Henry smiles at me as I throw out a quick, “See you in surgery!” and scamper through the door to catch up with Dr. Hallen down the hall. I bring my pace back down to a walk next to him, but he stops short again and turns to face me.

“You are at strike one, Dr. Penelope Kannery, and I operate on a two strike system, not three. Do not test me. The next time I see you will be in the O.R.” And with that, he’s off, not even giving me time to apologize for speaking to the patient.

I walk into the O.R. with my arms bent at the elbows take my place next to Dr. Hallen.

“Let’s see if you’re going to cash in on strike number two or succeed. I want you to make the initial incision,” he says as he hands me a scalpel. I do it with ease and fluidity.

“Okay Dr. Penelope Kannery, ever cut a breastbone?” My eyes light up at his words; I’ve never done it before on a live person, just cadavers.

“No, Dr. Hallen. It would be my honor to,” I say. He hands me the electric saw and I feel it again, the rush of the hospital. This is what I live for. I start my cut at the top of the sternum, avoiding the ribs.

“Now be sure to cut through the middle slowly. He’s old so his bones aren’t as healthy and you risk the chance of a rib cracking into the—” the BEEP of the breathing monitor interrupts him and I watch as the respiratory levels start to plunge.

“Get out of the way, Dr. Penelope Kannery. You not only just splintered a rib into his lung causing it to collapse, you just hit strike two. Get the hell out of my O.R.!” Dr. Hallen yells.

I stand at the small circular window of the scrub room as I watch him finish up Henry’s surgery with ease. Six hours later, both lung and heart are stable and he’s being wheeled out to the ICU for post-op monitoring as Hallen walks out.

“Two strikes, Dr. Penelope Kannery. You will now have to answer the consequences. So, what is your decision Dr. Penelope Kannery? Do you accept the consequence?” He asks as he scrubs out, and then opens another package of soap to scrub back in.

“Yes,” I reply.

The next thing I know, I’m lying on the very same table where Henry had just been. Dr. Hallen administers an epidural and lifts my scrubs to reveal my abdomen.

“I do not stand for mundane, avoidable stress in my surgeries, Dr. Penelope Kannery. Precision avoids stress. After this you will be as precise as you would be if you were operating on yourself—because you are.” He hands me a scalpel. I feel no rush, no “living for” feeling—rather a feeling of needing to survive. It was suddenly becoming a very dark Christmas.

“Remove your appendix, Dr. Penelope Kannery. Be precise.”