by The Cowl Editor on August 30, 2018

Arts & Entertainment

by Dr. Eric Bennett

Associate Professor of English

Life is too short to read everything. It may even be too short to major in American Studies. This column, brought to you by professors in AMS, highlights the books you simply cannot let pass, whatever your major. Start your list!

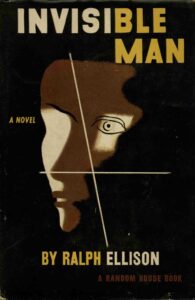

Ralph Ellison’s mid-twentieth-century masterpiece, Invisible Man, rides the harrowing logic of a nightmare. Each weird scene careens into the next with feverish inevitability. A dozen black teenagers pummel each other before a crowd of cheering white businessmen. A sharecropper rationalizes unspeakable acts. Elite powerbrokers torture the downtrodden with false promises. Yams go bad in the mouth. Street protests metastasize into psychedelic riots. A paint factory explodes.

Yet everything unfolds in the waking reality of a simple story. A nameless hero is expelled from his college in the south. He moves to New York, finds common cause with communists, loses faith in that creed, and vanishes underground. Through this most basic “kid leaving home” plot, Ellison captures in riveting detail the ill electricity of Jim Crow America.

In 1952, when Invisible Man first appeared, the world was still reeling from World War II and the genocidal racism that had permeated its driving ideologies. Many Americans believed that an account of a single life could stand in for all lives—could underscore our common struggles and downplay our incidental differences.

Mastering that vision, Ellison dramatized not only painful truths about African American history, but also the colorblind terrors and perplexities of modern existence.

It is all too easy to feel what his hero feels: at once powerless, stultified, and defiant as vast systems, hidden currents, pervasive norms, and random accidents tangle inextricably with the behavior of those around us and confuse our most intimate self-conceptions. “Who knows,” the narrator concludes, “but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?”