by The Cowl Editor on April 26, 2018

Campus

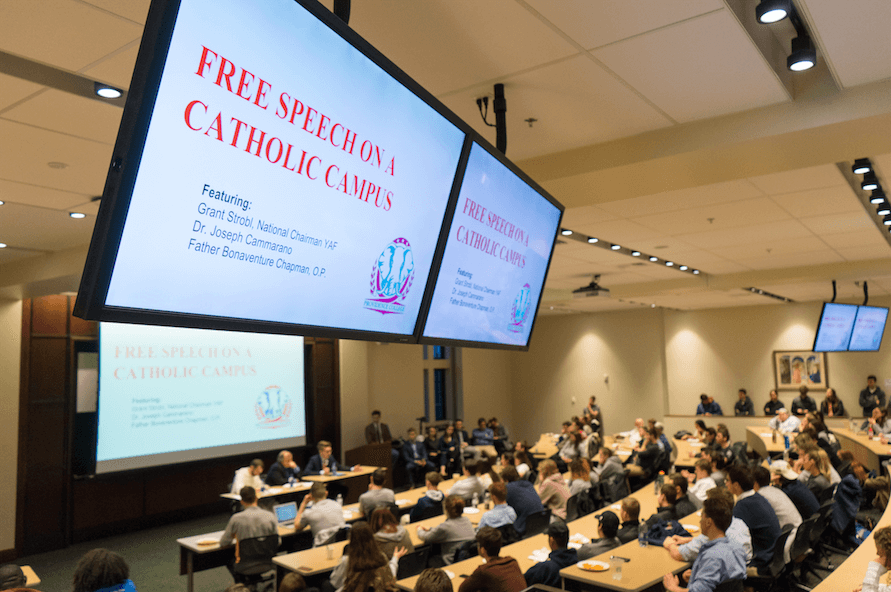

Final grades. Two words that either inspire a flurry of cramming or signal a reward for hours of hard work. With the semester drawing to a close, many students find themselves rushing to attend one of a variety of lectures deemed to have “extra-credit value” by their professors. Events, such as the recent “Freedom of Speech On a Catholic Campus,” fill quickly with students feverishly taking notes to write the standard one-page reflection for extra credit.

While these points may provide a safety net with final exams around the corner, the question of what value these assignments actually provide to students must be asked. Students are being taught to place the value of these events on the number of points to be gained rather than appreciating the message of the speakers.

The heart of this issue lies in the written reflections. Though they provide evidence that an individual was in attendance at a certain event, this is also measured by the attendance sheets that every student signs. In addition to demonstrating a physical presence, it is thought that these reflections will indicate whether or not a student was paying attention to the speaker.

However, the information required for one of these reflections can be obtained within the first 15 minutes of a presentation, as many students simply spit them back onto a piece of paper and hand it to their professor. Once enough information has been recorded, students have no real need to continue paying attention to the speaker, unless they are genuinely interested in the topic.

This brings us to the structure of these presentations and their two-part division. The first part, the main portion, is the actual speech. The second part is a question and answer session, during which students try to sneak out early. When this portion is announced, silence tends to settle as everyone looks to see who actually paid enough attention to form a question with depth.

It would seem that a better way of evaluating whether a student actually paid attention during such a lecture would be to capitalize on the question and answer session. This allows students to spend time focusing on the presentation itself, as opposed to seeking out small soundbites for their reflections and decreases the stress associated with having to rapidly accumulate as many facts from the lecture as possible to prove that one was paying attention.

Focusing extra credit assignments on participation during these lectures as opposed to the regurgitation of facts teaches an important skill. This skill is the ability to think critically about a claim being made and to connect it with other lessons a student has learned. By participating in such a presentation, students will use more brain power to engage the speaker’s claim in a dialogue.

In turn, this will make the presentation all the more memorable and applicable down the line. Reflection papers allow the student to recite facts that can easily be forgotten, but by participating in the lecture through a question and answer session, students will be more likely to carry the message of the presentation with them into later courses or post-college life.

It can be argued that there is not enough time for all the students in attendance to ask questions of the speaker, which is true. If all students were to ask questions, the presenter would be overwhelmed, and evaluating these questions would pose a potential issue to professors.

As before, the reflection pieces contain the key. The nature of these reflections must be changed if these presentations are going to provide any sort of lasting value beyond that of a couple points added to a grade.

Instead of simply focusing on what an individual learned, these pieces must attempt to continue the discussions started in the question and answer sessions. Whether it be simply making a connection between a presentation and a subject raised in class or debating the speakers’ claim, these papers must take on more active tones instead of reciting someone else’s presentation.

If any lasting value is to be derived from these presentations, a shift must be made in these evaluations from mindless summarization to active debate.