by The Cowl Editor on October 4, 2018

Opinion

by Andrea Traietti

Assistant Opinion Editor

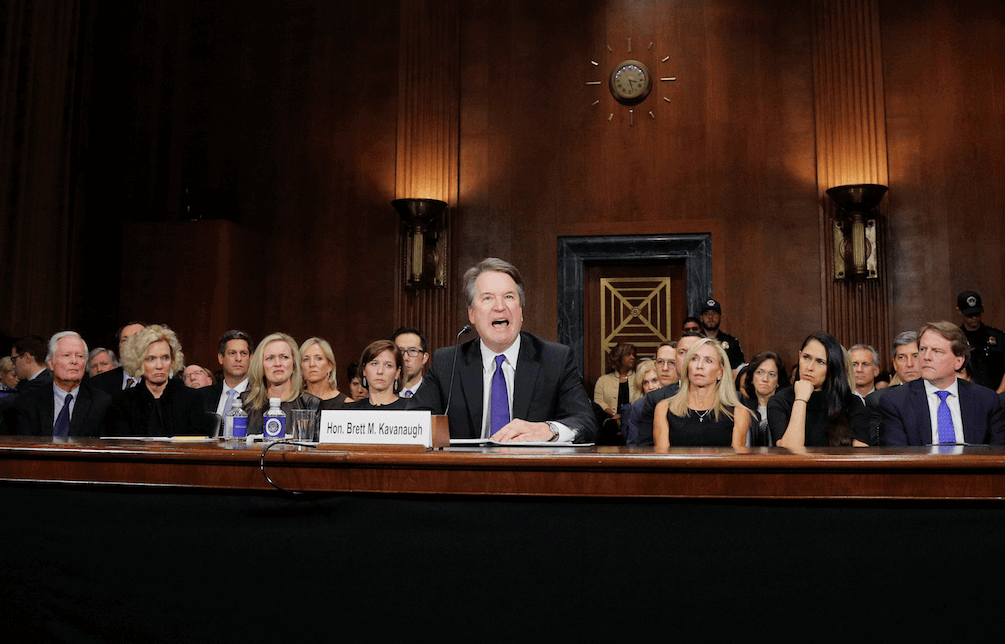

On his 1982 calendar, Brett Kavanaugh scribbled in his plans for July 1: “go to Timmy’s for skis w/ Judge, Tom, PJ, Bernie, Squi.” His yearbook entry is littered with references to beer consumption and drinking games. And while it can be easy to dismiss these warning signs as “boys being boys,” the fact that Kavanaugh sat in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee last week and literally said to senators—on multiple occasions— “I liked beer. I still like beer,” raises some troubling questions about drinking culture and entitlement in this country.

There is a moral responsibility to address this culture head on at a young age; Providence College is not exempt from this responsibility. High school and college shenanigans are not confined within the adolescent years, some kind of time warp where one’s actions do not matter and do not play a role later on in life.

Kavanaugh is proof. 36 years later, he is testifying under oath about his actions and habits in high school—and for good reason. Evidence of his arguably excessive drinking habits and abuse of alcohol could ultimately connect to his lack of recollection and his denial of the claims of sexual assault by Dr. Christine Blasey Ford. Without a doubt, the hearing and the ensuing FBI investigation are bringing to light the problem of sexual assault, but they are also exposing a different and not entirely unrelated issue: high school and college drinking culture.

Underage drinking is not just a problem for the reasons cited in sixth grade health class, i.e. stunted growth and slowed brain development. Those things are problems, but there is a bigger-picture, more widespread issue at hand: underage drinking is inextricably linked to entitlement. And entitlement is toxic.

Drinking in high school and college provides a feeling of freedom, a sort of invincibility, and the perverted comfort that you are not letting “the best years of your life” go to waste. But it is time to recognize that even this use of alcohol really is abuse. It is so problematic that instead of viewing Kavanaugh’s drinking as a serious problem, many are looking at it as a sign of his patriotism and his masculinity.

It is not patriotic, it is not manly, and it certainly is not innocent fun. College students are not invincible, and anything that makes them feel as such is an explicit danger not only to those who participate in drinking, but to the community at large. It is a toxic culture that feeds directly into the culture of toxic masculinity—and if Kavanaugh’s testimony last week had one central theme, that would be it.

This toxicity, this entitlement does not go away, it lasts a lifetime. And that is exactly why it needs to be prevented from the start. PC plays a role in this prevention. In 2017 alone, there were 459 on-campus property “disciplinary referrals” for liquor law violations. In the previous year there were 397. This is a 15 percent increase.

It is entirely unrealistic to expect, assume, or demand that college students in the 21st century, even those under 21-years-old, abstain from drinking alcohol. The use of alcohol on college campuses has always been present, and always will be; however, the boundary between use and abuse is not a fine line—it is a bold one. And it is one that has extremely dangerous consequences personally, socially, and culturally when crossed.

That being said, PC clearly needs to change its approach to these violations. Perhaps a violation of the law merits more than a referral. Two things must change. First, PC needs to reform its alcohol education policy because the 15 percent increase in the last year alone shows that whatever is being taught now is not effective. Second, there needs to be serious repercussions for violations, and those repercussions must be understood and internalized by the student body at large.

Drinking has become such a central tenet to the college experience that it is hard to picture life without it. But because the habits—both good and bad—established during these years are the ones that stick for a lifetime, we need to reevaluate drinking’s role in our culture. We need to sever the link between drinking and the sense of entitlement because that connection only fuels the fire of toxicity in social circles and empowers young adults to act with no inhibitions.