by Sara Conway on March 4, 2021

Film and Television

by Sara Conway ’21 A&E Co-Editor

*Warning: this article mentions rape.

What is family?

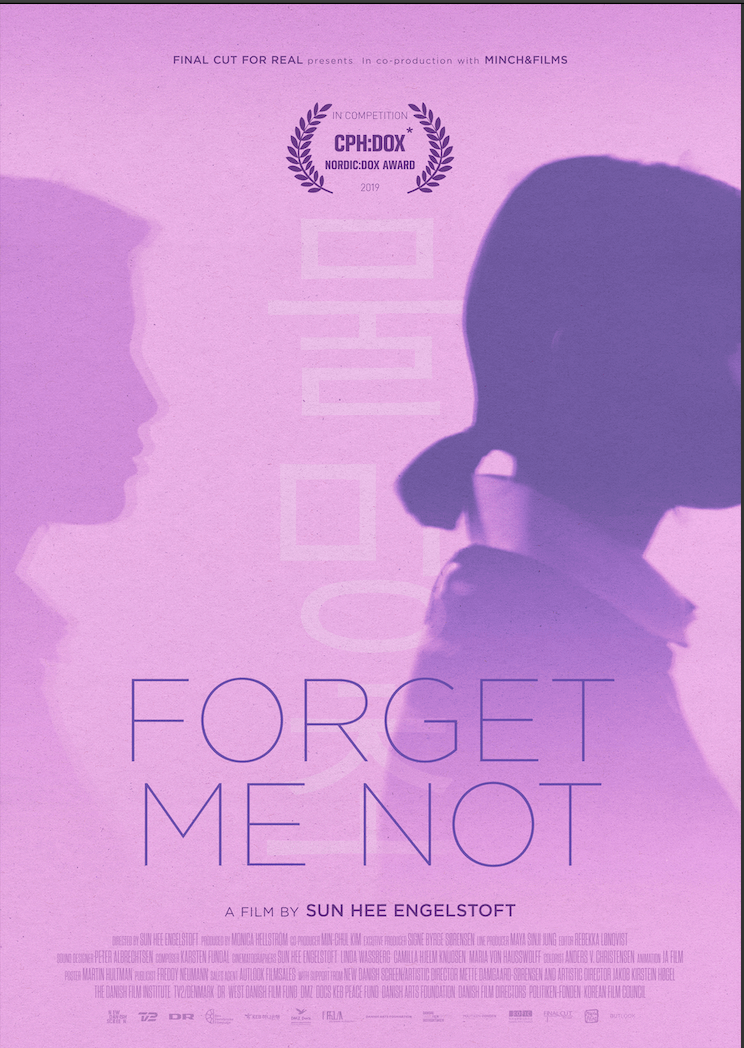

Minari, directed by Korean-American filmmaker Lee Isaac Chung and released this past February, and Forget Me Not, directed by Korean-Danish documentarian Sun Hee Engelstoft and released in March 2019, seek their own answers to this persistent question through their art.

Minari tells the story of a Korean-American family who move to rural Arkansas from California in the 1980s. The father, played by Steven Yeun, buys land in hopes of pursuing his dream of farming American soil—he is one step closer to reaching his American dream. While the film is playing in select theaters, A24, the distribution company, began virtually screening Minari earlier in February.

The Yi family battles with the rocky transition, the intense isolation of being in the countryside, the other ups-and-downs of rural life, and the introduction of their grandmother from Korea (Yuh-Jung Youn). Throughout the course of the film, they reach their own understanding of family and how they are all tied together in the end. As stated on their official Twitter, Minari is a “story about where we come from, and where we choose to grow.”

Director and writer Lee Isaac Chung drew from his own childhood to create Minari, as his story is one that is similar to the Yi family’s. As Yeun emphasized in a question and answer session, the actors do not have to “explain [their] identity or culture as [their] only defining qualities” with the narrative Chung has brought to the big screen.

A slice-of-life narrative, Minari captures a distinctly Korean-American story, where the characters’ Korean identities are never sacrificed. Indeed, there are many sacrifices made, such as the parents leaving their children at home while they go to work, but their culture is not a piece of their lives that gets left behind.

Most of the film is in Korean with English subtitles. However, there sometimes is a casual blend of languages, as Anne and David—the Yi children—also speak fluent English, a unique part of the Korean-American experience. There are moments when a question is asked in one language, but the child, or parent, answers in the other, or a word or two would be sprinkled in the middle of a conversation, but it flows easily back to the other language. This mode of communication articulated in the script was clearly written by someone who understands this cadence that possesses no rhyme or reason but what is spoken in the moment.

Furthermore, Jacob, the father, sets out to plant Korean vegetables in his newly acquired land. His singular focus is working the “American” land and succeeding in providing for his family while creating something of his own. Jacob is so intent on this dream that he brushes aside the grandmother’s decision to plant minari—a vegetable that looks similar to parsley—by the small river found on their large piece of land. She brought seeds from Korea with her, and soon enough, her minari thrives, while her son-in-law’s farming endeavors uproot challenge after challenge.

As is clear from the title, the film centers around the theme of the minari. If broken down literally in Korean, “minari” translates to “water vegetable,” a nod to where the plant is grown. In the film, Halmeoni scatters her seeds on the riverbank in the woods, some significant distance from the Yi’s house. It is here, off of the beaten path, that the thin, small, but tenacious plant flourishes.

David, the youngest Yi, is like minari: he is present in a majority of the scenes in the film, and viewers see him as a mischievous, kind, and shy kid with a heart murmur that makes his family worry. He also is the one family member who has never been to Korea and has a different experience navigating his “Americanness,” as the United States is the only place he has known. While smaller and maybe weaker than others—particularly with his heart murmur—David, like the minari plant, finds a way to hold his ground while beginning to understand his, and his family’s, identity.

Similar to Minari, the March 2019 documentary Forget Me Not tells a hidden story of family. Weaving together English, Danish, and Korean, Korean-Danish filmmaker Sun Hee Engelstoft records life in a shelter for unwed pregnant women located on Jeju Island, South Korea. Called Aesuhwon, the shelter is run by a woman named Mrs. Im, who fights for the mothers and their children to stay together in a society that wants to erase any indication of their situations and their existences. Engelstoft and her camera follow three women as they struggle against familial and societal pressures, navigate pregnancy, and try to find an answer to the impossible question: keep their children or give them up for adoption?

Forget Me Not is a fitting title, just like Minari is an apt name for the aforementioned film. Engelstoft connects the personal documentary to her own history, as she is an adoptee, and her mother stayed at the shelter she records. With this undercurrent, and the stories that the filmmaker reveals, “forget me not” packs an emotional punch, if not solely on the literal level. However, the forget-me-not flower also possesses associations with remembrance, loyalty and faithfulness despite separation, and represents a connection through time. Despite the mothers and their babies being severed from one another, trauma is endured on both sides, and a memory persists despite the passing of time.

The women at Aesuhwon have been ostracized from their own families, and it had been deemed necessary that they be hidden from society. Their families give curious outsiders excuses as to where their daughters have gone. In addition, as the documentary shows, most of the time it is the parents of the women making the final decisions about what to do with the babies.

Engelstoft documents the journey of a woman she calls “B.” In the end, the baby of B was registered under the woman’s father’s name. While the two would grow up together, B could only acknowledge her child as her sister; the small one was now her father’s because others would not question him having an affair but would socially execute B if they knew the full truth. Even in the house, she cannot hold her baby. The parents of B force an inexplicable distance between their daughter and her child.

The most heart-wrenching moment of the documentary was the conclusion of a girl’s memory with her child at Aesuhwon. The last story Engelstoft shows is one of a 15- or 16-year-old who got pregnant after being raped. The girl gives her child to a local Jeju Island pastor and his wife. Although she is close enough to visit her baby, uncertainty and hesitancy plagues her. Even when the baby is nestled in the arms of the pastor’s wife as they are getting ready to leave Aesuhwon’s grounds, the girl holds on for one more moment. Her anguish is undeniable.

Engelstoft and her hand-held camera trails behind the girl as she makes her way back to her room, her sobs reverberating throughout the empty halls. Viewers watch as Engelstoft lays her camera on the floor—no sounds save the girl’s cries are heard—and goes over to the corner where the girl is huddled and hugs her. What words can be uttered at this moment?

Forget Me Not carefully blurs out the faces of the women and their children to preserve their anonymity. However, they are not blurs. Rather, Engelstoft takes painstaking efforts to maintain their humanity through the smoothed out and indistinguishable features.They are human beings behind those masks.

Both Minari and Forget Me Not assert the resilience and the dignity of the people they feature. Their stories are told in the realest ways possible—the good, the bad, the ugly, the beautiful. No matter the obstacles, no matter the amount of times these people are knocked down to their knees, they somehow find it in themselves to stand up one more time. And so they begin again.