by The Cowl Editor on November 12, 2020

Opinion

A Democracy of Hypocrisy: The Existence of the Electoral College Exposes Contradictory Ideals

by Sienna Strickland ’22

Opinion Staff

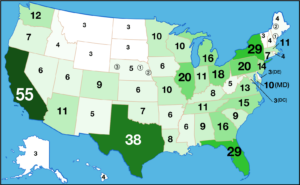

Last week, the American public watched anxiously to see who would prevail in the presidential election—a victory earned by securing at least 270 of the 538 electoral votes. In this election, Joe Biden won the majority support of the Electoral College, and it just so happens that he won the popular vote as well. Although this was the case for this particular election, electoral votes and the popular vote do not always align; a candidate can win the presidency even if they do not win the popular vote, so long as they garner 270 votes from the Electoral College. In consideration of this fact, the question arises: is the United States’ voting system flawed? After investigating the history behind the creation of the Electoral College, it becomes clear that our nation needs to reevaluate whether this system allows for true democracy.

The men who established America were a ragtag bunch—at least, compared to their formidable cross-Atlantic opponents—who were forced by the urgency of their treacherous insurgency to be quick on their feet, lest they lose their heads.

After achieving an unlikely victory over the British in the Revolutionary War, the founders were not out of the woods. Rightfully weary of unrepresentative monarchical rule, but also historically aware of the grave dangers of unruly democracy, they were tasked with something seemingly impossible, and as we will explore, inherently contradictory as a result: finding a happy balance between the two extremes. The strong central authority that a monarchy provided was necessary, but the democratic diffusing of power amongst the people—to avoid the catastrophic uprisings that crumble oppressive systems—was too.

In other words, America, although a democracy on paper, is not really a full-fledged democracy in practice, as it gives people a say, but not too much. This would not be a scandalous opinion to the founders if they were to hear it; this inconsistency on their part was intentional. Perhaps the most overt example of this purposeful contradiction of America’s self-purported democratic values is the existence of the Electoral College.

The Electoral College is an institution which insulates the presidential election from coming into direct contact with the American people, and is full of electors that the American people do not themselves elect to represent them.

To understand why this institution exists, we must first understand the following: America is a tale of two approaches—revolutionary ideals, met with conservative implementation. If the Declaration of Independence is a revolutionary document, then the Constitution is a restrictive one.

At the Philadelphia Convention in 1787, a mere four years after the conclusion of the Revolutionary War, delegates met to discuss matters of America’s governance. Here, at the event in which the Electoral College was first created, these two approaches were on full display.

At the time, no other nation in the world directly elected its chief executive, so this radical resolution raised red flags amongst some of the delegates; America had already pulled off the feat of the century in successfully seceding from Britain, so it did not want to push its luck.

Dr. Joseph Cammarano, political science professor at Providence College, who is teaching a seminar called “President as Elected Monarch” in the spring, discusses the creation of the Electoral College as a contradictory compromise the delegates themselves were not overly-pleased with:

“It is very specifically, intentionally undemocratic, and was very clearly put in as a compromise, primarily to prevent the direct election of the president. It was put in because of the elitist notions of faithless electors, who thought it their duty to protect the outcome of the presidency from the masses. It is among the least democratic parts of our constitution.”

The Electoral College was a last-minute resolution, essentially scraped together by a group of tired men desperate to come to an agreement. One question remains: why did they believe direct election was so radical at all? Dr. Cammarano touches upon their motivations by labeling them as “elitist.”

With bodies still coating the battlefields and the ink fresh on the parchment, America was in a vulnerable position not only as a newborn nation, but as one that doubled as a democracy. Although we commonly accept democracy as one of the best modes of government, this was not always considered to be the case. Pure democracy, or citizens having complete say, has been critiqued since antiquity for being ruled by people too uneducated to make informed decisions for themselves, nevermind the nation. This rationale surely fueled such elitist assumptions, but were reasonable concerns for America at the time considering that significant portions of the population were illiterate.

Now, centuries later, this is no longer the case. We are privy to improvements in our educational system, voting laws that have granted more access to our citizens, and have valuable hindsight our founders were not privy to. We are not in the same crucial timeframe they were. Instead of curbing the weight of the citizen’s vote, we should invest even more in our education systems, including civic engagement.

The Electoral College is in need of modification if it is to remain a part of our nation’s presidential election process. If we are to keep the Electoral College, there should at the very least be more transparency regarding who these electors are, and at most a process for us to elect our electors. If we do not, calling ourselves a republic—a government in which representative officials are elected by the people—is simply inaccurate.