Tag: David Salzillo Jr. ’24

A Totally Unnecessary Rant About Hallmark Movies

by David Salzillo Jr. '24 on December 8, 2022

Opinion Staff

Opinion

This article might be upsetting both to regular viewers of Hallmark movies (if such people really do exist) and to children who still believe in Santa Claus. To the latter group, I offer my sincerest apologies.

Ah, Christmastime—the season for caroling, hot cocoa, and…bad Hallmark movies. Why humanity must suffer through that last one is a mystery. Yet here we are: the filmmakers (one uses that term VERY loosely) behind these cinematic travesties are at it again.

Technically, they were at it again long before now. Hallmark’s chief executives seem to believe that Halloween marks the first day of the Christmas season. Forget waiting until after Thanksgiving; forget about waiting until the first of November. These people have managed to outdo those infamous radio stations that play Christmas music 24/7 from November to January. Ugh. Doesn’t Hallmark have any sense of shame?

Now, if the movies were halfway decent, maybe some of this shove-it-down-your-throat-until-you-die-in-a-Christmas-induced-coma consumerism could be forgiven. But alas, trying to find a halfway decent Hallmark movie is like trying to catch Santa Claus on Christmas Eve. Where does one even begin? How about with the filmmakers’ complete lack of effort? Seriously, do they care about what they are doing, insofar as it is not bringing them a paycheck? Don’t they understand that snow on someone’s clothes will melt after a few minutes, as opposed to staying there for an entire scene? And don’t they understand that people generally swallow after drinking coffee? If you ever have the displeasure of watching some of these movies, you will be able to find countless other egregious errors like these. It does not take a Francis Ford Coppola or a Martin Scorsese to get these things right.

Then there’s the incessant presence of hot chocolate, cookies, and bake-offs. The bake-offs in particular irk me: I have never seen nor been to a bake-off in my life, yet somehow they always manage to be a central plot point of Hallmark’s Christmas programming. They would make you think that bake-offs are a fixture of the average American’s life. They have to keep up that small-town aesthetic.

This brings up another falsely represented aspect of Hallmark movies: their inane platitudes about small-town life. To be sure, I don’t hate small towns, nor do I hate people who like small towns. Living in a big city is not paradise on Earth. Yes, big cities have pollution, traffic, and, worst of all, people. But must their messaging be so clumsy and obvious? By the way, where are the homeless people in these small towns? Where is the trash? Most people have been to enough small towns in their lives to know that they have not eradicated poverty and garbage.

And don’t get me started on those corny love stories or that stupid derivative rom-com music that plays whenever the main love interests of the stupid plot first meet in the stupid way that they always do. Couldn’t these writers come up with a better way for the true loves to meet, without the clumsily concocted pratfalls? Hallmark characters appear more accident-prone than even the worst of klutzes.

But why bother getting so upset about this? Because I am upset for you, dear reader. I am upset that you must be subjected to this for the next three months or more. As the great writer Ralph Ellison said, “who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?”

Or maybe not. In that case, try to develop better taste in movies.

An Open Letter to President Biden

by David Salzillo Jr. '24 on November 17, 2022

Opinion Staff

Editorials

Dear President Biden,

Congratulations. As I am writing this, your party has managed to hold the Senate, and still—as of Nov. 14—has a fighting chance of holding the House. Your instincts have proven correct: above and beyond political disagreements and the public’s view of your presidency, the majority of voters expressed their desire to prevent government by the people, of the people, and for the people from “perishing from the earth.” Yes, it was a close call, and too close for me to be content with. However, the majority did speak with a resounding voice, bringing a decisive defeat to election deniers and other anti-democratic rhetoric within the Republican Party. For now, the threat of authoritarianism in America has stayed.

I, for one, give you your proper credit. When others in the party did not, you had faith in the working people across this country making the right choice. And when Democratic pundits fell into hysterics about “red waves,” you kept calm. But now we have won. And, like Robert Redford in The Candidate, we must ask this question: “What do we do now?” The battle is not over, and the stakes are higher than ever.

We see the rise of “new and improved” Trumpian and anti-democratic politicians like Ron DeSantis. We see one of our two major political parties still consumed by election denialism and political primaries that reward these election deniers. Worst of all, we see that the Republican Party establishment is, as it stands now, far too morally bankrupt to repudiate Trumpism once and for all. Even if Republican Party leaders cast Trump aside, they will only cast him aside because he “didn’t work” like they wanted him to—like a child throwing away a dysfunctional toy.

Our politics cannot survive like this for much longer. One might say the Republican Party will implode if it continues on this path. On the other hand, it might not. It might instead take us on more of a “winding road” toward authoritarianism. We cannot take the chance.

You want to be a great president. What’s more, you need to be a great president for our republic to survive. To overcome such fundamental threats to our democracy, nothing less than a great transformation of American society is necessary. And when the problem is our politics and, more to the point, our politicians, then a top-down transformation appears even more appropriate. Consider the example of history too. Each time we have had a “crisis of confidence” in our democracy—whether during the Civil War or the Great Depression—a great President has led us closer to the Promised Land.

Like Thomas Paine once said of the American Revolution, “we have it in our power to begin the world over again.” But that requires an ambitious agenda, on par with Johnson’s Great Society and FDR’s New Deal. Of course, I can hear your advisers saying, “But we have done that. Haven’t you heard about our historic investments in infrastructure? And what about our historic initiative to get Medicare to negotiate prescription drug prices?” I respond simply: the infrastructure investments, historic as they are, are like pouring a bucket of water onto a California wildfire. Likewise, Congress passing a bill allowing Medicare to negotiate prescription drug prices, while appreciated, was long overdue.

What I am saying is go bigger. Think bigger. President Johnson could have made historic progress on civil rights without passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Why? Because other presidents had not been able to do much of anything on that front. And President Johnson could have made historic investments in combating poverty without the Great Society. All he had to do was invest $1 more than Kennedy or Roosevelt had. But that is not what he did. History rightly celebrates Johnson for his vision. Without that type of thinking, would anybody have the chance to enjoy the benefits of Medicare and Medicaid?

Nonetheless, I realize you face certain practical limitations. By all means, acknowledge them. For my part, I will be brutally honest: this is going to be hard, and it at times will seem impossible. It will take some masterful politicking, just as it did in Johnson’s time. Even then, advancing a bold legislative agenda is no less impossible than it was to get the Civil Rights Bill through a Senate with segregationists and the filibuster.

I am confident the American people will follow a good vision, with results that positively affect their everyday lives. Voters may not be able to fact-check as well as they could, but they can read “the signs of the times.” If your Administration passes the bills, your Administration will reap the rewards.

It’s getting there that’s the problem. You have a possible Republican House, you have at least 50 Democratic Senators, and you have Senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema. What could you possibly do with that?

It may look like you got the wrong deck of cards for a great presidency. Nevertheless, there is still some hope. But not in conventional compromising. Those days are over, for better or worse. I propose to you, as St. Paul did to the Corinthians, a “better way.” Consider again Johnson’s Civil Rights Bill. As Jonathan Rauch notes in “How American Politics Went Insane,” getting that bill passed meant getting it past House Republican leader Charles Halleck of Indiana. How? Was it through a passionate debate of the issues or principled arguments for the equality of all people? No. A NASA research grant for Halleck’s district was enough to do the job. This approach to politics might make one cynical, but not me. Instead, it shows how even political self-interest can lead to monumental change.

I will add this: per the old cliché, “nothing succeeds like success.” Republicans will not compromise on their own; the people must force them to take their places at the negotiating table. If your Administration can pass more and more ambitious legislation—even if by one vote—and people start to like what you are doing, then Republicans will have to compromise. Self-interest and self-preservation will drag them along. As Martin Luther King Jr. said, “A genuine leader is not a searcher of consensus but a molder of consensus.” President Johnson likely would have agreed. Compromise, indeed, is not exactly the right word to describe how Johnson passed the Civil Rights bills; arm-twisting is perhaps the more accurate term. Johnson used every method of persuasion he had to get his party and those in the other party onboard.

Obviously, you might not want to imitate everything Johnson did. But a little more arm-twisting may do some good, especially if Democrats gain a seat in the Senate and especially if somehow Democrats hold the House. Arm-twisting, aggressive public relations efforts, and some good old-fashioned backroom negotiations. They have never failed the traditional politician, and it may be fatal to go back to the “let’s split everything down the middle” model of compromise. Instead of splitting things down the middle (after all, what is the middle now? The halfway point between you and Marjorie Taylor Greene?), we must push the middle over.

Thomas Paine once said, “we have it in our power to begin the world over again.” And if we do not take advantage of that power, then others will. And we may not like the world they give us.

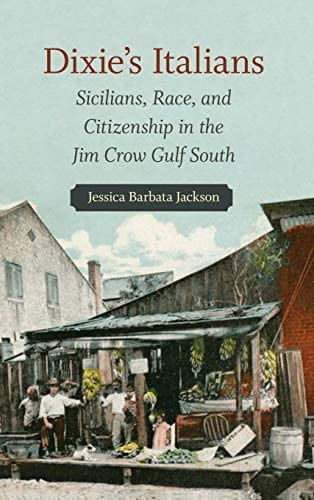

Immigration and Collective Amnesia: A Reflection on Last Week’s Lecture by Dr. Jessica Barbato Jackson

by David Salzillo Jr. '24 on November 3, 2022

Opinion Staff

Editorials

The early history of immigration to the United States is not the story of the melting pot, but the vortex. In our American history courses, we often hear about the endless cycling of this vortex. It starts with a group of immigrants that come to America for the promise of freedom, independence, and a better life, and it ends with the descendants of those same immigrants seeking to deny others the same opportunities. Why? Because the vortex sucked them in and caused them to embrace the very same prejudices that once justified discrimination against their ancestors. It is a remarkable cycle of forgetfulness, and it has not died out in the 21st century. After all, weren’t the Irish once looked down upon as primitive papists and ape-like Thomas Nast caricatures? Weren’t the Italians once considered a horde of mafiosos and stupid peasants? And aren’t immigrants today supposedly invading our country with their drugs, their crime, and their rapists?

How do we fail to see the vortex at work? Does the irony escape us? How else could Stephen Miller, the descendant of Eastern European Jewish immigrants, be the founder of a group that warns of “a giant flood” of immigrants? I must ask: is this giant flood the same flood that brought Miller’s family to our shores?

Now, I am not trying to set aside the practical question of what to do about illegal immigration. But we must put this rhetoric in perspective: groups like Mr. Miller’s are calling for restrictions on illegal and legal immigration. Why? Well, the rhetoric, as it always has, speaks for itself. Miller’s concern is not with stopping crime, nor achieving both a compassionate immigration system and an orderly one: it is about swatting off “the horde”—as if migrants were a bunch of vultures waiting to feast on America’s carcass. This method of dealing with immigration, first of all, neglects the practical consequences of not welcoming more immigrants. Japan is the perfect example of this: its restrictive immigration policies have led to a shrinking and aging population. America’s politicians need not make the same mistakes. Instead, they must realize that these floods that Miller and his ilk complain about are like the annual floods of the Nile: they are necessary to “enrich the soil.”

But I digress. The repel the horde mentality neglects to define who “the horde” consists of. This is where the story of Italian immigrants in the South is particularly instructive. In Dr. Barbata Jackson’s book Dixie’s Italians, she describes how Italian immigrants and Italian-Americans were—to New Orleans residents and those across the rest of the South—an invasive foreign species. They faced mass lynchings and constant suspicions about their abilities to be true American citizens. Does all this sound familiar? It should. Late 19th and early 20th century America had a more elaborate racial hierarchy than 21st century America, with ethnic whites like Italians and others of the Mediterranean race placed lower on this racial hierarchy than other whites.

However, those of Southern Italian descent were still whites. Official U.S. records categorized them so, and thus gave them legal rights denied to non-whites. These legal privileges are undeniable and distinguish Italian-Americans from other historically disadvantaged groups in America. And the most violent forms of discrimination against Italian-Americans, while no less abhorrent than violence against people of other races and ethnicities, did not last far beyond the first few decades of the 20th century. As bad as anti-Italianism was, it was only a small taste of the discrimination that others confronted.

But that will never justify the existence of the vortex. Italian-Americans should know better than to imitate the behavior of those that discriminated against their ancestors. For a culture centered around the family, what better way to honor them than by preventing others from forgetting about their struggle for acceptance? To do that, and to stop the vortex, Americans must learn to see not “the horde,” but “the immigrant.”