Tag: Sara Conway ’21

Capturing the Intricacies of Climate Change, Sisterhood, A Decaying World, and the Worth of Humankind

by Sara Conway on May 6, 2021

Literature

The Ones We’re Meant to Find by Joan He

by Sara Conway ’21 A&E Co-Editor

Cee knows two things: she woke up on a deserted island three years ago, and she does not remember anything, except that she has a sister named Kasey. And she needs to find her. Meanwhile, Kasey, declared a “STEM prodigy,” wants a solution. Humans are rapidly destroying the earth as she knows it, and the coveted eco-cities that float above can only protect humanity for so long. Two timelines; two stories; two sisters. One twist-filled sci-fi novel that tackles climate change, the end of the world, and the ever-lingering question of what it means to be human.

Meet The Ones We’re Meant to Find by Joan He. Released on May 4, this book is He’s sophomore novel, coming two years after her debut novel, Descendant of the Crane. Prior to the publication of The Ones We’re Meant to Find, The Cowl spoke with He about the inspiration behind her latest book, writing Cee and Kasey’s characters, and the part oceans play in The Ones We’re Meant to Find.

—–

Hi Joan! Thank you so much for speaking with me today for The Cowl. Let’s just jump into it then: How did the idea for The Ones We’re Meant to Find (TOWMTF) first come to you?

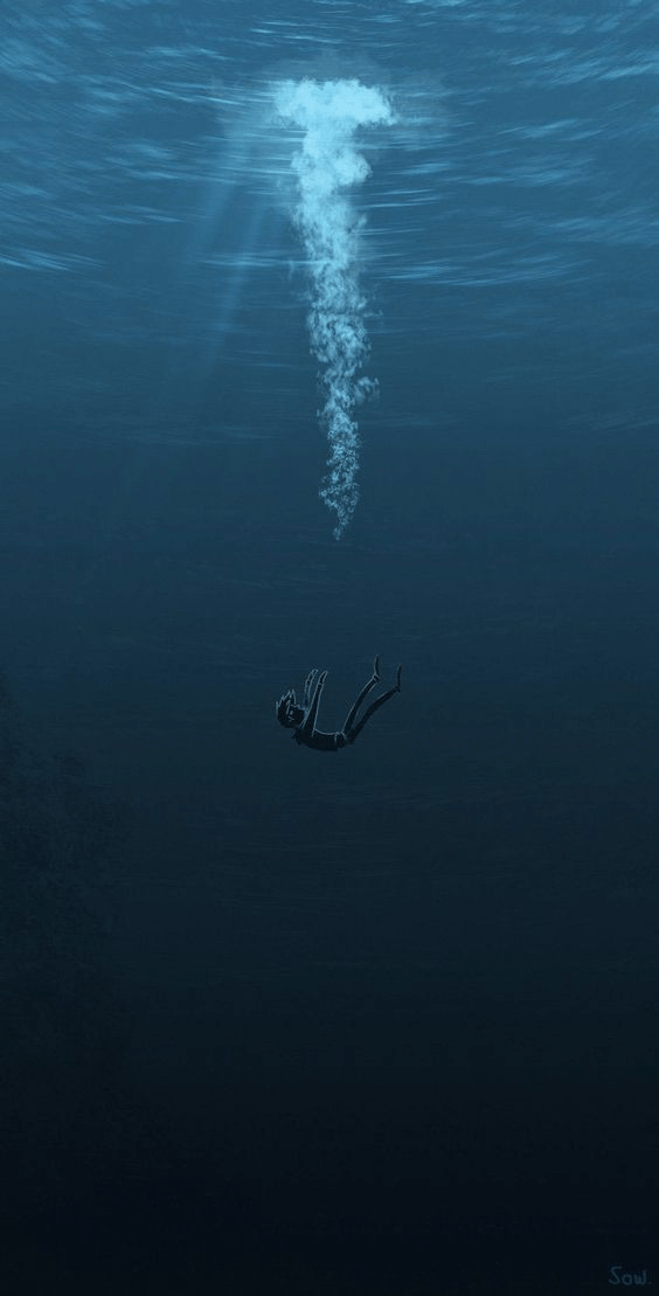

The initial idea came to me in a dream: I had a very vivid image of a girl diving to the bottom of a sea, in search of something or someone. As I tried to figure out the “what,” my mind went back to some of my favorite YA [young adult] Dystopians I’d read as a teen, such as The Hunger Games and Legend. They left a deep impression on me, particularly in how they signaled the relatability of their main characters. A single scene with a younger sibling, for example, could frame a protagonist as human and vulnerable before they went on to topple dictatorships or save the world. I wanted to subvert that. What if, I wondered, the girl in my dream is searching for her younger sister, but that sister is more than a storytelling device? And so came the heart of the story.

The title, The Ones We’re Meant to Find , has such a beautiful rhythm to it (and this line actually appears in the story). Was the title always this?

Yes—this was the title from the start, and I’m grateful it survived the many drafts, all the way to the final book.

TOWMTF is your sophomore novel. Would you say there was a difference in your writing process and approach to this story (sci-fi fantasy) compared to your debut, Descendant of the Crane (high fantasy)?

Descendant of the Crane was actually the book that forced me to become a plotter. Anyone who’s read it can probably understand why writing it without a plan was NOT a good idea. But even for DOTC, I knew the middle from the start, as well as how I wanted it to end. Same for TOWMTF. So the overall approach didn’t really differ even though TOWMTF is in a different genre. I will say though that the second book is harder solely because you have more voices in the room than you would when working on your debut.

One thing most readers probably notice is the distinction in point-of-view as the chapters alternate between Cee and Kasey. Why did you choose to write Cee’s chapters in the first person, while writing Kasey’s in the third person?

As mentioned above, part of the inspiration behind the book comes from the expectations set up by the early YA dystopias. Cee, as a character, is based off of a lot of the protagonists I found within the pages of those stories, and has many of the traits that, simply by appearing often enough, would be deemed almost requisite for a traditional YA hero. Likewise, I also wanted Cee’s POV and writing style to reflect that “canon” so that the eventual subversion of it would be more impactful. Hence, the first-person present tense. As it happens, it’s also well suited to her character.

Meanwhile for Kasey, I wanted to respect her character and give her the distance that she would personally have wanted from the reader. Her deepest thoughts aren’t something that anyone can or should be privy to. At times, even Kasey has a hard time accessing how she really feels when she’s overly aware of how she should feel.

What was it like finding and writing Cee and Kasey’s characters/voices (I’m especially curious about Kasey and her intelligence level)?

Writing Cee was pretty easy; there’s a lot of existing fodder and framework for her sort of character, and I never really felt like I was pushing the envelope with her voice. Don’t get me wrong—I loved writing Cee and had a lot of fun with her, but her voice felt like a safe choice.

Kasey, on the other hand, was much more of a challenge—and not just because of her intelligence. Time and time again, I wondered if I should give her a little more. Make her a bit more sarcastic, put more sass and bite into her voice, give her more opinions, more attitude, more flair. But none of those add-ons would be true to Kasey. I had to sit with the insecurity of writing a character who I knew was missing a lot of charm and wit. Her being smart, after all, doesn’t make her any less awkward. But it felt right that I would feel insecure about her, because if Cee is the kind of the character I would have wanted to be as a teen, Kasey is much closer to who I was. I didn’t feel like I fit in or had the most interesting things to say. I still feel the same insecurities, to this day. I hope that Kasey can show readers that there is space in books for characters like Cee, but also space in books for characters like her.

How and why (non-spoiler or super vaguely) did you choose each character’s name?

Cee’s name came to me first—the reason behind it is a spoiler, so I will not say. Once I had Cee’s name, I then tried to pick a name for the sister that would be a good complement for it.

The ocean plays a crucial role in TOWMTF (and the gorgeous cover definitely emphasizes this). Why the sea?

Because of that earliest dream I had, I always knew that the setting would be by the ocean. It worked out, because in the plot, the ocean serves as a huge obstacle both characters must overcome to find their way back to each other. As I continued to develop the story, the ocean also became more and more thematically relevant to the heart of the book and the world. It’s a crucial part of our biosphere. The earliest life forms originated from it, including our human ancestors. It’s a place of birth, and also of a place of death. Radioactive isotopes can travel from one continent to another by way of the currents. It connects all of us, no matter where we live. We’re dependent on it, and it also depends on us. It mirrors the conflict in the story perfectly, and adds to the mystery of the atmosphere.

Pollution, mass climate change, climbing death counts, and intense natural disasters create the backdrop of destruction for TOWMTF—this is the world the characters live in. There must have been points when you became overwhelmed with the state of their life (and its connection to ours) and the questions they were forced to confront. How did you strike a balance with the overwhelming, and how did climate change become the focus of TOWMTF?

Because of the twist, I knew I needed the world to be ending in the story. For what reason? I wondered. Since I wanted the focus to be firmly kept on the sisters’ relationship, I tried to pick the most plausible and intuitive cause. Climate change, therefore, felt like the obvious choice.

I first drafted the book in 2017, so of course I couldn’t have foreseen the parallels as clearly as I did in 2020, when I was revising it. There were definitely moments where I got overwhelmed—not by the story, but by the facets of human behavior I knew to be true. I’d seeded them into the book, and the moment I heard COVID was in the US, as early as February, I had a sinking feeling. We weren’t going to be able to contain it. If our best stopgap measure was relying on everyone to stay in and wear masks, that wasn’t going to happen on a wide enough scale to make a difference; it’s incredibly hard to get people to care about something that isn’t immediately threatening them. So, yeah, that was overwhelming. But the story in the book actually gave me hope. I knew I had to share it. Because as flawed as we are as a species, we are also capable of incredible things.

What songs and images come to mind when you think about TOWMTF?

I’m pasting an image below that comes closer to capturing the image I saw in my dream. As for songs: “TIME” by Hans Zimmer, “On the Nature of Daylight” by Max Richter, and the entire Gattaca soundtrack, but especially “Departure.”

Former Associate Editor-in-Chief Katie Torok ’20

by Sara Conway on April 22, 2021

Literature

The Intersection of Storytelling, Publishing, and Sales

by Sara Conway ’21 A&E Co-Editor

“I’ve loved stories my entire life.” Katie Torok ’20 sits in a comfortable armchair, books on floating shelves peeking into the video frame behind her.

Regardless of the medium or format of these stories, part of that love came from being an only child. Torok adds, “Through books, I found that I had siblings I could look up to, whether that was Katniss in The Hunger Games or any of the characters from Perks of Being a Wallflower. I felt completely immersed in these characters, and they felt so real.”

Storytelling is at the heart of Torok’s leap into the publishing industry; in fact, this is at the center of many critical decisions, she reflects. Storytelling is “why I was an English major; and why I joined The Cowl: to help tell stories, whether they were out of Providence College or the Providence community.” At the end of the day, Torok wanted to break into the publishing industry because of “storytelling and [to give] people and their stories a shot.”

Torok is currently a sales assistant on the National Accounts team at Penguin Random House Publisher Services, the client division of PRH, based in New York City. Her team works with over 50 independent publishers across the United States and London, where they “help small unique books get into larger accounts.” These accounts include Amazon, Books-A-Million, Barnes & Noble, and wholesale clubs, which Torok mostly deals with, such as Costco, BJ’s, and Sam’s Club. She now has this goal from working in sales: “to get the super small niche stories out to everyone.”

But let us take a few steps back to when Torok was accepted into the Columbia Publishing Course. It is February 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic was still barely a concern in our minds; the location is The Cowl office in the lower level of Slavin.

Those who are familiar with The Cowl office know that the beanbag chairs are way too comfortable for their own good. Torok was sitting in one when she noticed that she was getting a call from New York City. The amount of spam calls she had been receiving were quite frequent, so Torok almost did not pick up. Luckily, at the last moment, she did. And it was the call to pick up. Shaye Areheart, the director of the Columbia Publishing Course, was on the other side of the line to congratulate Torok on being accepted. “I was quite literally speechless and continued thanking [Areheart], even though my voice was cracking as I was on the verge of bursting out in tears,” Torok remembers. After that she ran back into the office, since she took the call in the hallway behind McPhail’s, and told Kerry Torpey ’20, last year’s editor-in-chief, the good news. The rest of The Cowl office was there to celebrate with Torok following Torpey’s larger announcement of the acceptance.

Storytelling is “why I was an English major; and why I joined The Cowl: to help tell stories, whether they were out of Providence College or the Providence community.”

However, Torok’s publishing journey began before the Columbia course. She saw publishing “as a job” in her sophomore year when The Cowl’s then editor-in-chief, Marla Gagne ’18, mentioned that she was accepted into the same program. Then in Torok’s junior year (fall 2018), she received the coveted opportunity to intern in the Children’s Marketing and Publicity department at Simon & Schuster UK through her Boston University study abroad program. This experience exposed Torok to the inner workings of a major publishing house. One of her tasks was mailing out advanced reader’s copies to social media influencers and tastemakers or other people who Simon & Schuster believed could “get a little buzz going about the book.” Torok also created content for social media, supported in-house author events, and developed a week-long blog tour for a major frontlist title.

The next year, Torok dove into another critical aspect of the publishing industry: literary agencies. In the publishing process, representation by a literary agent is often the first step to getting traditionally published. Through her internship at McIntosh & Otis, Torok was the “first eyes” on a manuscript, mostly middle grade and young adult, since her position was focused, again, on working with the children’s department. “I would read through the slush,” which was her main task, and Torok elaborated that if anything caught her eye, she would pass it on to her manager, an assistant to a literary agent.

These experiences and her genuine love of stories led her to the Columbia Publishing Course, a direction to go in after graduation. Formerly known as the Radcliffe Publishing Course, this program has two locations: one in New York City and one at Oxford University in the UK. CPC covers a wide breadth, from book publishing to digital and magazine publishing through lectures, seminars, and workshops over a period of six weeks. Alumni of the course brought their stories and expertise through engaging panels. In the publishing industry, Torok emphasizes, there are often “a lot of unanswered questions, so [CPC] tried to be as transparent and supportive as possible” and encouraged students to make the most of this unique program.

Although Torok participated in the course remotely—the first time CPC was conducted this way—Columbia was still an incredibly valuable experience. An undeniable difference, however, was seen in the way networking happened. Usually this was integrated in all aspects of the course, since students typically live in Columbia’s on-campus housing with five or six other roommates who are also in the program. There were traditional networking opportunities available, such as natural face-to-face conversations and casual encounters during happy hour. This shift is “something the entire world has been faced with, but especially the class of 2020 and 2021.” Networking virtually poses new challenges, as Torok considers, “how do I come across politely over email; how do I keep in contact with them; how do I find that balance that is so critical?”

When asked about her takeaways from the CPC, Torok immediately answered: “the network.” She added, “At the end of the day, as big of an industry publishing is, it is so small at the same time, you can probably find most connections through one or two degrees of separation.” Torok’s newfound Columbia network “provided a really incredible support system outside of [her] Providence College one,” which is composed of Megan Manning ’18, a sales manager at Simon & Schuster, and Marla Gagne ’18, a marketing coordinator at W.W. Norton.

Torok also realized that “it’s okay to be interested in only one or two parts of publishing,” citing that she “learned quickly that if you think you’re passionate about something, there’s most likely someone else who is 30 times more passionate about it than you.” When the Columbia program began, Torok thought she might go into children’s marketing and publicity, since she had internship experience related to it. However, she remembers a moment during a group project when they were a children’s publishing house: “Immediately my group is talking about a book that went on sale a week ago. They already read it,” Torok laughs. It was then that she had a realization: “I don’t think I’m cut out for this side of the industry.”

Torok’s last takeaway is “figuring out what works best with your personality and being honest about yourself.” Just like with her original aspirations to go down the children’s publishing route, she had to be “honest” with herself and give, in her case, sales a “chance.”

Torok was first introduced to sales through Manning when they connected at a NYC PC networking night in December 2019. However, Torok became serious about sales after listening to a panel at CPC where she witnessed a younger alumnus briefly pitch a book. “That was the coolest thing to me,” Torok said, eyes dancing. “You can just pitch people a book in seconds and soon after they’re saying, ‘Oh my God, I have to read this now.’”

Eventually, Torok found her “sweet spot” in sales. “I was passionate about sales, which not everyone was interested in at Columbia.” Through her job, she interacts with both her client publishers and the book buyers at wholesale clubs. Torok also “want[ed] to be talking and collaborating with people across a wide team,” which she definitely gets to do in her sales position.

“On The Cowl we told both the smallest stories and the biggest world news stories, and that’s exactly what we do in publishing.”

Torok’s dedication to books and her job is obvious, which led to my question, “What makes you excited to get up and start working?” The answer comes easily: “I love our books.” Since Torok’s team manages a diverse range of books from Stephen King to keto cookbooks to the No. 1 NYT Bestseller, White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo, they “work with every type of book.” She adds, “The fact that I get to touch so many different books is refreshing.” On top of that, Torok enjoys the challenges, such as “trying to figure out how to get certain books into Costco without having too many returns,” Costco being a place that shoppers do not usually go to buy books. She also emphasizes that “we are a division of PRH that won’t stop growing,” which is exciting in its own right.

Furthermore, Torok’s team and their support makes it easy to start working every day. She points “100 percent” to her experience with The Cowl for “understanding and developing a support system.” The Cowl and her current team both “create an environment where communication flows” and mutual learning occurs, giving a foundation of transparency. In both teams, everyone “can be honest and upfront, and have fun.”

Torok draws another connection between the two: “On The Cowl we told both the smallest stories and the biggest world news stories, and that’s exactly what we do in publishing.”

An interview with a publishing professional is not complete without a few book recommendations. Recent books Torok loved are Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid and The Ex Talk by Rachel Lynn Solomon. Others she recommends from her client publishers are The Art of Hearing Heartbeats by Jan-Philipp Sendker, a mystery set in Burma; They Called Us Enemy by George Takei, a graphic novel memoir about Takei’s experience in the Japanese internment camps during World War II; and Juliet the Maniac by Juliet Escoria. Torok received the latter title when she officially began working for Penguin Random House. When new employees came into the office—before COVID-19—there was usually a stack of book recommendations waiting for them on their desks from others. However, because of the pandemic, this was not possible for Torok, but each of her team members hand-selected a book for her. A week before she started, this mystery box of books was delivered to Torok’s front door.

At the end of the interview, Torok emphasized there is no “one way” of breaking into the publishing industry; every professional you speak to will have a different route and story of how they got to be where they are. Torok’s advice for those interested in publishing, however, is relatively simple: “Get your hands on books, magazines, text, or storytelling in any way that you can.”

Former Cowl Editor-in-Chief on Teaching English in South Korea, Connecting With Others, and Hearing Their Stories

by The Cowl Editor on April 15, 2021

Features

by Sara Conway ’21

A&E Editor

It had been a long 15 hours for Kerry Torpey ’20. Flying across the world to South Korea in order to teach English—and during a global pandemic, no less—was no joke.

There was the proper paperwork to put together before departing from the United States, then there was the 15-hour flight itself. But one of the last hurdles was the temperature check after landing at Incheon International Airport.

Since her trip was in February, Torpey wore a sweater and her winter coat for the flight. Unfortunately, when mixed with her backpack—which was “15 pounds heavier than it was supposed to” be—dragging her luggage through the airport, and the general stress of traveling overseas during a global health crisis, Torpey’s temperature was just slightly higher than what the authorities at the airport considered acceptable.

Cue her desperate efforts to cool down once she was in another line for those who had not quite made the temperature cut. The backpack was dropped, the coat was shed, and her hair was up. So close and yet so far.

Although Torpey would not leave for South Korea until February 2021, she began the tenuous process of acquiring the proper paperwork for her journey in July 2020. “Everything’s in the context of COVID-19,” Torpey said, detailing that if something was slightly off, you could be sent back to the U.S. before you even stepped outside of Korea’s airport. Plus, before she could board the plane in the U.S., Torpey needed a negative COVID test, so she spent her last month in America self-quarantining. Hence why she “wasn’t able to breathe” until she actually got to South Korea, made it through the airport gates, and was safely quarantining in her room. And although Torpey has been in Seoul teaching for a little more than a month, she said that it did not feel real quite yet.

Currently, Torpey is teaching English in a public school in Seoul, South Korea, where she has 22 different classes of students ranging from grades four through six. She applied for a teaching position through English Program In Korea, a program with the Korea National Institute for International Education, which is under the umbrella of the Korean Ministry of Education. While Torpey’s application was handled by EPIK, her employer is actually the Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education, since EPIK recommends specific applicants to education offices across South Korea that then hire the teachers themselves.

Pursuing a degree in education was on her mind during her time at Providence College, but Torpey was unable to double major in it alongside her English studies. But she remembers Cowl copyeditor Jennifer Dorn ’18, who received a Fulbright Scholarship to teach English in the Czech Republic. That moment in her sophomore year, Torpey notes, is when she really started looking into teaching English internationally. As to why she wanted to teach abroad—and specifically in South Korea—Torpey had a few attachments to the country, one being a high school friend who resides there.

Another was the vast difference between American and Korean culture. “That intrigued me beyond no degree,” Torpey said. She wanted to be in a place where she would have to learn, adapt, and immerse herself, especially with the language hurdle, although Torpey emphasized that Hangul, the alphabetical system that forms the basis of written Korean, is “potentially one of the greatest inventions of all time” (no disagreements there). But this cultural difference simultaneously holds infinite possibilities of exploration and fostering a deeper understanding: “the most human connection you can have with someone is talking about where you come from.”

As an English major, a staff writer, and an editor of the Arts & Entertainment section of The Cowl, and later Editor-in-Chief, these experiences built solid foundations for Torpey to pursue teaching English. She joined The Cowl September of her freshman year and moved up to an editor position by the end of the year, which further developed her “confidence in [her] ability to write, to edit, and [her] grasp of the English language.” While she was too late to double major in education, Torpey did take courses such as Educational Psychology taught by Dr. Kevin O’Connor, which focuses on classroom management and formulating better insight into the kids in your classroom.

She also has been around educators her entire life. Torpey’s grandmother was a teacher; her sister is a teacher; and her aunt is a dean of a law school. In addition, she volunteered in her sister’s second grade classroom for about five years, so Torpey is familiar with the school environment for younger learners.

These experiences also gave Torpey confidence as she prepared for her new role as an English teacher in a new country. She stressed that the schools and their relationship with their native-speaking English teachers are varied, and it depends on where someone ends up. Torpey’s school gives her a fair amount of creative freedom as she structures her lessons around the textbook and adds her own personal touches.

The nucleus of Torpey’s preparation, however, was research. Years of research. She is naturally still learning, but Torpey made sure that she was culturally aware and respectful of Korean customs, many of which are drastically different from those in the United States. Torpey emphasized that it all boils down to respect and understanding what is rude and what is polite, particularly for a culture that is founded on respect and hierarchy such as South Korea. For example, in Korea, one has to give and receive things with two hands.

Torpey is also the youngest teacher in her school, which is a role within itself. Since she is a foreigner, she generally is not expected to know certain customs. However, Torpey’s “effort to learn” demonstrated an awareness and a willingness that deeply respects the country, the history, and the culture of the place in which she now resides.

Language studies was a necessary part of preparations as well. Torpey used online resources including YouTube, a program called Talk to Me in Korean, and various apps. While she was in quarantine in Korea, she took an online class. Currently, Torpey is looking for a course in Korea, noting that she often learns better in a classroom setting.

While she has been studying the Korean language for some time, Torpey does get stressed about speaking. Although it is a persistent hurdle, she is aware that she has to push herself to use the language because “the only way you’re going to get better is if you use it.” In the end, yet again, “it is the effort that counts.” And Torpey does understand more than she gives herself credit, which she acknowledges, recounting, “Sometimes my co-workers will say something to me in Korean, and it’s funny, so I’ll laugh.” Torpey chuckles as she remembers their surprised reactions.

When I asked her about her expectations for South Korea and for teaching, Torpey said she had none. “There’s just so many unknowns that how can you possibly have any expectations?” Torpey muses over how she is usually a planner, but the journey to South Korea, including the 15-hour long flight—and the experience living in the country—has shown her that you can plan all you want, but those same certainties can be uprooted just as quickly. However, despite having no expectations, Torpey again emphasized respect: “take everything with grace and respect for others and yourself.”

This has guided Torpey from the day she landed in Korea and beyond. Now, a month into teaching, she is “grateful” and excited to go to work every day. However, it all “comes back to the students and their willingness and eagerness to learn and how open they are.” The first day was like how most are when they meet someone new. Her students were “a little shy, a little intimidated,” and Torpey remembers that they were a bit “fascinated” by her since Korea is a relatively racially homogenous place.

Despite the differences in age, culture, and experiences, mutual interests bridge Torpey and her students, who call her “Kerry Teacher.” On the first day, she created an introduction PowerPoint and because she mentioned that she played basketball for a while, she now plays with some other teachers on Wednesdays.

This foundation of openness that Torpey set from the beginning is what characterizes her classroom. By being “welcoming and accepting,” she encourages a mutual exchange that then builds an “inclusive and comfortable” space. Although her students do not speak fluent English, “we can still have conversations in which we are making connections with one another over similar interests in sports or movies or music,” Torpey added. In essence, a “human-to-human connection” is created. She gave the example of one of her lesson games called “Stay Alive,” which made learning “I have a cold” a lot more fun for her sixth graders, many of whom like playing video games. The lesson was designed so students can gain a life, lose one, or, if they were physically in class, steal a life as they worked to improve their writing and speaking skills. Listening to her students and taking note of what they like allows her to “find games that cater to their interests,” thus making the process of learning English more engaging for everyone.

While Torpey is the teacher, there is a great deal that she has already learned in her (short) time in South Korea. “We are all such small fish in a big sea,” she reflected, drawing the conversation to her walks through Olympic Park in Seoul, which she often finds many older Koreans strolling through as well. “The oldest generations here either remember the Korean War or grew up in the years that followed, in which the country was in a serious economic struggle as they tried to create a new nation,” Torpey continues. She emphasizes that the “rich history of South Korea can be seen on every corner in Seoul, and it is important not to forget this history when thinking about South Korea, which many now associate with pop culture.”

However, as Torpey notes, “the people who are here have stories from all of those time periods,” from the Korean War to its economic boom. As the time inches closer to 11 p.m. in South Korea, Torpey thoughtfully adds her personal reflection: “It’s made me realize how important it is for all of us to try and broaden our worldviews.” She emphasizes that there are so many stories ready to be told at our fingertips, and “Korea is a country that is incredibly rich with stories.”

Stories are the common thread: “With the pandemic, when you aren’t around people as much, you kind of lose that humanness a little bit and that connection and that closeness with people.” Teaching in a totally new country, while there are numerous challenges, presents a unique opportunity, where there are new stories and new histories to be found.

There is clarity in Torpey’s eyes as she concludes, “While I can’t speak the language very well, I still feel like there’s so much to appreciate here within the culture, within the people and the stories that they have. That’s why it’s important to me to study the language very hard, too. I’m not going to be an expert by the next year, but I want to be able to talk to people and hear their stories.”

One of Torpey’s favorite Korean words is ha-ru, meaning “one day.” Maybe one day Torpey will be able to speak to the people of Korea and hear their stories in their native language. But even now, she is connecting on a fundamental human level as a teacher, learning about the Korean culture, and getting to know her students—the next generations—and their own stories. And that is a start.

Let’s Rant: The Low Strategies of the Grammys

by Sara Conway on March 18, 2021

Music

Manipulating BTS and Their Fan Base Helped Drive Views

by Sara Conway ’21 A&E Co-Editor

Let’s talk about the Grammys. Specifically, about BTS and the Grammys. The septet was nominated for Best Pop Duo/Group Performance, their first nomination as a group, which came with priceless reactions from the members. It is no surprise that the members of BTS have had their eyes on the Grammys for some time; with each year, the seven crept a little closer to the stage and a nomination. Rapper Suga (Min Yoon-gi) is well-known for voicing these dreams, as he did during an interview with Jimmy Fallon in 2018. A year later, the group presented H.E.R. with the Best R&B Album award, while their album Love Yourself: Tear was nominated for Best Recording Package. In 2020, they performed “Old Town Road” with Lil Nas X—another step forward. At this year’s Grammys, BTS were both nominated for a Grammy (which they did not win) and performed their own music on the award show’s renowned stage.

“Dynamite,” their only song sung completely in English, received the honor of a Grammy nomination. I will be the first person to tell you that “Dynamite” is a far cry from showcasing BTS’s strengths and skills as artists. They are talented musicians, and their hard work cannot be doubted. Have you listened to the final verse of “Outro: Tear,” where J-hope tears through his lyrics, the backing orchestra rapidly hurtling towards the emotional breaking point of the track? Have you ventured to take a peek at the complex storyline of their The Most Beautiful Moment in Life and Love Yourself eras? Have you seen the verses their rappers have written, like RM’s lines from “Spring Day”: “Holding your hand, I go to the other side of the world / I wish to end this winter / How much longings must fall like snow / before that spring day arrives.” And for goodness sake, their debut song “No More Dream” is about the intensity of the South Korean educational system and challenges listeners to dream. In the face of what BTS has created in their seven—almost eight years together—“Dynamite” barely scratches the surface. No, strike that. “Dynamite” stays at the surface, or more notably, stays at the surface geared towards the standards of western pop (mostly its radio).

I am not frustrated because BTS did not win the Grammy. It is that the Grammys used the groupʼs clout—a.k.a. their massive fan base named ARMY—to promote the award show, pushing BTS’s performance forward to capture more attention. In the end, however, the Grammys relegated the announcement of Best Pop Duo/Group Performance (among other higher profile categories) to the pre-show livestream on YouTube, an odd choice considering this category is usually presented at the ceremony. What the Grammys said with this decision is that BTS is not worth more than what their popularity and their fans can bring in views. And, boy, did the views come. 12.6 million views on the livestream, to be exact. Oh, and BTS’s first Grammy performance was dead last, closing the show.

There are promises of the Grammys becoming more “diverse” and more “inclusive,” but time and time again, stunts like this are pulled. “Work harder, and you will be rewarded,” they say. “Work harder and prove to us that you are worthy of our attention, and then we will talk.” Yet this “award” that is just out of reach and given by a predominantly white (and American) standard is just an illusion.

So, Grammys. I’m seriously “sick of all your trash.”

Film Spotlight: Minari and Forget Me Not

by Sara Conway on March 4, 2021

Film and Television

The Smallest Are Sometimes the Most Resilient

by Sara Conway ’21 A&E Co-Editor

*Warning: this article mentions rape.

What is family?

Minari, directed by Korean-American filmmaker Lee Isaac Chung and released this past February, and Forget Me Not, directed by Korean-Danish documentarian Sun Hee Engelstoft and released in March 2019, seek their own answers to this persistent question through their art.

Minari tells the story of a Korean-American family who move to rural Arkansas from California in the 1980s. The father, played by Steven Yeun, buys land in hopes of pursuing his dream of farming American soil—he is one step closer to reaching his American dream. While the film is playing in select theaters, A24, the distribution company, began virtually screening Minari earlier in February.

The Yi family battles with the rocky transition, the intense isolation of being in the countryside, the other ups-and-downs of rural life, and the introduction of their grandmother from Korea (Yuh-Jung Youn). Throughout the course of the film, they reach their own understanding of family and how they are all tied together in the end. As stated on their official Twitter, Minari is a “story about where we come from, and where we choose to grow.”

Director and writer Lee Isaac Chung drew from his own childhood to create Minari, as his story is one that is similar to the Yi family’s. As Yeun emphasized in a question and answer session, the actors do not have to “explain [their] identity or culture as [their] only defining qualities” with the narrative Chung has brought to the big screen.

A slice-of-life narrative, Minari captures a distinctly Korean-American story, where the characters’ Korean identities are never sacrificed. Indeed, there are many sacrifices made, such as the parents leaving their children at home while they go to work, but their culture is not a piece of their lives that gets left behind.

Most of the film is in Korean with English subtitles. However, there sometimes is a casual blend of languages, as Anne and David—the Yi children—also speak fluent English, a unique part of the Korean-American experience. There are moments when a question is asked in one language, but the child, or parent, answers in the other, or a word or two would be sprinkled in the middle of a conversation, but it flows easily back to the other language. This mode of communication articulated in the script was clearly written by someone who understands this cadence that possesses no rhyme or reason but what is spoken in the moment.

Furthermore, Jacob, the father, sets out to plant Korean vegetables in his newly acquired land. His singular focus is working the “American” land and succeeding in providing for his family while creating something of his own. Jacob is so intent on this dream that he brushes aside the grandmother’s decision to plant minari—a vegetable that looks similar to parsley—by the small river found on their large piece of land. She brought seeds from Korea with her, and soon enough, her minari thrives, while her son-in-law’s farming endeavors uproot challenge after challenge.

As is clear from the title, the film centers around the theme of the minari. If broken down literally in Korean, “minari” translates to “water vegetable,” a nod to where the plant is grown. In the film, Halmeoni scatters her seeds on the riverbank in the woods, some significant distance from the Yi’s house. It is here, off of the beaten path, that the thin, small, but tenacious plant flourishes.

David, the youngest Yi, is like minari: he is present in a majority of the scenes in the film, and viewers see him as a mischievous, kind, and shy kid with a heart murmur that makes his family worry. He also is the one family member who has never been to Korea and has a different experience navigating his “Americanness,” as the United States is the only place he has known. While smaller and maybe weaker than others—particularly with his heart murmur—David, like the minari plant, finds a way to hold his ground while beginning to understand his, and his family’s, identity.

Similar to Minari, the March 2019 documentary Forget Me Not tells a hidden story of family. Weaving together English, Danish, and Korean, Korean-Danish filmmaker Sun Hee Engelstoft records life in a shelter for unwed pregnant women located on Jeju Island, South Korea. Called Aesuhwon, the shelter is run by a woman named Mrs. Im, who fights for the mothers and their children to stay together in a society that wants to erase any indication of their situations and their existences. Engelstoft and her camera follow three women as they struggle against familial and societal pressures, navigate pregnancy, and try to find an answer to the impossible question: keep their children or give them up for adoption?

Forget Me Not is a fitting title, just like Minari is an apt name for the aforementioned film. Engelstoft connects the personal documentary to her own history, as she is an adoptee, and her mother stayed at the shelter she records. With this undercurrent, and the stories that the filmmaker reveals, “forget me not” packs an emotional punch, if not solely on the literal level. However, the forget-me-not flower also possesses associations with remembrance, loyalty and faithfulness despite separation, and represents a connection through time. Despite the mothers and their babies being severed from one another, trauma is endured on both sides, and a memory persists despite the passing of time.

The women at Aesuhwon have been ostracized from their own families, and it had been deemed necessary that they be hidden from society. Their families give curious outsiders excuses as to where their daughters have gone. In addition, as the documentary shows, most of the time it is the parents of the women making the final decisions about what to do with the babies.

Engelstoft documents the journey of a woman she calls “B.” In the end, the baby of B was registered under the woman’s father’s name. While the two would grow up together, B could only acknowledge her child as her sister; the small one was now her father’s because others would not question him having an affair but would socially execute B if they knew the full truth. Even in the house, she cannot hold her baby. The parents of B force an inexplicable distance between their daughter and her child.

The most heart-wrenching moment of the documentary was the conclusion of a girl’s memory with her child at Aesuhwon. The last story Engelstoft shows is one of a 15- or 16-year-old who got pregnant after being raped. The girl gives her child to a local Jeju Island pastor and his wife. Although she is close enough to visit her baby, uncertainty and hesitancy plagues her. Even when the baby is nestled in the arms of the pastor’s wife as they are getting ready to leave Aesuhwon’s grounds, the girl holds on for one more moment. Her anguish is undeniable.

Engelstoft and her hand-held camera trails behind the girl as she makes her way back to her room, her sobs reverberating throughout the empty halls. Viewers watch as Engelstoft lays her camera on the floor—no sounds save the girl’s cries are heard—and goes over to the corner where the girl is huddled and hugs her. What words can be uttered at this moment?

Forget Me Not carefully blurs out the faces of the women and their children to preserve their anonymity. However, they are not blurs. Rather, Engelstoft takes painstaking efforts to maintain their humanity through the smoothed out and indistinguishable features.They are human beings behind those masks.

Both Minari and Forget Me Not assert the resilience and the dignity of the people they feature. Their stories are told in the realest ways possible—the good, the bad, the ugly, the beautiful. No matter the obstacles, no matter the amount of times these people are knocked down to their knees, they somehow find it in themselves to stand up one more time. And so they begin again.

New Year, New Semester, New Watchlist

by Patrick T Fuller on February 4, 2021

Arts & Entertainment

A Wealth of Netflix K-Dramas to Add to Your Queue

by Sara Conway ’21 A&E Co-Editor

Here we are again. Barely a month into 2021, and this new year has already slammed us with a series of historical events: the Jan. 6 Capitol attack; the swearing in of President Biden; the GameStop fiasco which occurred during the last week of January; and, of course, the world still battles COVID-19.

Escaping into a story, regardless of medium, is desperately needed. Netflix is always there, but what to watch after bingeing the high-profile shows such as The Queen’s Gambit and Bridgerton? Look no further than to the abundance of original Korean dramas—or K-dramas, as they are better known—on Netflix.

In 2019, the Korea Creative Content Agency (KOCCA) reported that the United States “accounts for five to six percent of the international viewership” of K-dramas, or about 18 million viewers. As Korean entertainment has gained more international attention, including from the American mainstream, so has the content, such as K-dramas, steadily increased and become more widely available on platforms like Netflix.

Before jumping into watching a K-drama, a few basics of the genre must be explained. Firstly, unlike American TV shows that often span across several series, K-dramas are generally one season, ranging between 16 and 24 one-hour episodes. This is part of the allure of K-dramas: their storylines have a conclusion, and in their compact form, they are highly binge-worthy (not to mention the addictive antics that are characteristic of these dramas).

Another basic element: there will be tropes. But the tropes make the stories so much fun. For example, if it is a romantic comedy (or not), there is a high chance that the romantic leads used to be childhood friends and somehow forgot this fact. Past trauma also tends to play an important role in the present drama that slowly rises to the surface (a K-drama is not complete without some family trauma). The characters find a way to confront this trauma while also looking good. Long trench coats and turtlenecks are a classic K-drama look—and for good reason.

K-dramas would not be K-dramas without their twists, and sometimes a viewer really has to suspend their belief in reality. On that note, if there is no body, then the person who was said to be dead is most likely not dead. They will reappear again, almost guaranteed.

Lastly, K-dramas cover every genre under the sun. You want a historical story? Great. Watch Hwarang: The Poet Warrior Youth about the Silla Dynasty, 57 BC–935 AD. What about a cute college romance? Tons out there. A semi-believable-and-also-hilarious drama about a CEO accidentally ending up in North Korea? Let me tell you about Crash Landing on You.

Released in 2019, Netflix’s original show, Crash Landing on You, follows Yoon Se-ri (Korean last names are written first), a successful businesswoman and CEO of her own beauty brand. One day, while testing a new hang glider suit, a strong storm suddenly sweeps in and knocks Se-ri into none other than North Korea. Her antics to try and escape are both hilarious and frustrating, as upset plans and close calls abound. Family drama back in South Korea, a North Korean army captain, and a loyal band of side characters make things interesting for Se-ri as she attempts to cross the border again and again.

About two months after Crash Landing on You finished airing, a new Netflix original hit the streaming platform: Extracurricular. In this darker K-drama, a typical wallflower-straight-A high school student is not all that he seems. Oh Ji-soo is the middleman in a complicated side hustle that makes bank, which helps him save up money to go to college. However, things start to spiral out of control when his “part-time job”—which may be or not be illegal—is discovered by a fellow classmate.

Ethical undercurrents are also foundational in Hospital Playlist, another Netflix K-drama released in 2020. Maybe hospital shows are not what one wants to watch now, but Hospital Playlist sets itself apart from the copious medical dramas available through its tight friend group of doctors who first met in medical school. Also, they form a band together, practicing after work whenever they can. You will never hear Pachebel’s “Canon in D” the same way.

Finally, It’s Okay to Not Be Okay (2020) explores mental health, trauma, and family with a dark fairytale twist. Ko Moon-young and Moon Gang-tae are a famous picture book author and a caregiver in a psychiatric hospital, respectively, who literally collide in a hospital where Gang-tae works and Moon-young is a guest speaker. As their lives become more and more entangled, which is further complicated because they knew each other as children, both take steps towards emotional healing, beginning with art and stories.

If you need some laughs, moments in which reality is tossed out the windows, or shows in which friends, family, and romance all intersect with unique plotlines, K-dramas are an absolute must-watch.

BTS’s Virtual Concert, Map of the Soul ON:E

by The Cowl Editor on October 29, 2020

Arts & Entertainment

The Show that Won Big with Creative Technology

by Sara Conway ’21 A&E Co-Editor

BTS’s most recent title track, “On,” has a lyric that goes, “Can’t hold me down cuz you know I’m a fighter,” and no line fits the seven-member group better than this one. Not much has deterred the band, who is arguably the most famous group in the world right now. In the past two weeks, BTS has won the Top Social Artist Award at the Billboard Music Awards (BBMAs) for the fourth year in a row, held the No. 1 and No. 2 spots on Billboard’s Hot 100 (for “Savage Love” with Jason Derulo and Jawsh 865 and their English single, “Dynamite,” respectively)—a feat only four other artists have accomplished—and successfully held a two-day online concert amidst the chaos of COVID-19.

The band’s original Map of the Soul world tour was supposed to kick-off in Seoul this past April, but all of the dates were eventually canceled. Then, on Aug. 13, Big Hit Entertainment, BTS’s company, announced Map of the Soul ON:E (MOTS ON:E). This new concert had an in-person component for those in South Korea, but due to COVID-19, fans around the world attended the concert virtually on Oct. 10 and 11. The change of plans did not limit BTS and their crew from executing above-and-beyond performances.

MOTS ON:E tickets were sold through Big Hit’s app called Weverse. For once, the BTS ticket buying experience was not accompanied by the fear of the event selling out. The live concert was in 4K or HD if fans were utilizing the multi-view, starting at 6 a.m. EST on Oct. 10 and 3 a.m. on Oct. 11. Big Hit also added a delayed viewing option that would open a few hours after the live version had ended. According to Billboard, almost one million fans from around the world attended this BTS weekend concert.

The innovative sets and technology utilized for MOTS ON:E created a memorable online concert experience, especially for those who had never attended one before. MOTS ON:E included multi-view live streaming, extended reality (XR), and augmented reality (AR). Following the concert, fans had the option of purchasing entrance into the virtual BTS Exhibition Map of the Soul ON:E (오,늘) to continue enhancing their concert experience.

BTS concerts are well-known for their high-quality performances and creative use of technology, and MOTS ON:E was no different. Out of the four stages they used, the group started with the one that featured a jutting rock, a symbol taken from the music video of “On,” which was also the opening song of the concert. This stage captured the metaphor for all of the mountains BTS has overcome together over the past seven years and for the current struggle of COVID-19. However, just as the lyric from “On” says, BTS fought through these challenges, especially seen in how they held a concert for themselves and their fans in the middle of a pandemic.

The innovation did not stop there. During leader RM’s solo song, “Intro: Persona,” a giant version of him appeared with the help of AR technology. Rapper Suga started the performance of his track, “Interlude: Shadow,” in a horizontal hallway of flexible white screens, reminiscent of the song’s music video, where people behind them leaned in to touch him, causing the space to grow even smaller. The youngest member, Jungkook, multiplied himself through screen projections during his solo, “My Time.” An infinite number of Jungkooks were reflected behind him, following the real artist’s movements and creating a funhouse effect.

BTS showed off the capabilities of the XR stage through their performances of “DNA,” “Dope,” and “No More Dream,” their debut song. Fans saw the seven members dance their famous “DNA” choreography in a brightly colored outer space scene, and their performance of “Dope” inside of a racing retro elevator, which occasionally stopped in different worlds like a snowy mountain landscape. “No More Dream” was less visually overwhelming than the other two but no less engaging and exciting. Playing off of the Korean meaning of BTS’s name (“Bangtan Sonyeondan” translates to “Bulletproof Boy Scouts”), this stage featured flying bullets that seemed like they would hit the seven members and explosions that erupted at their feet as they sang about not having a dream.

The closing song of the concert, “We are Bulletproof: the Eternal,” also referenced BTS’s name and linked their journey with their ARMY (“Adorable Representative M.C. for Youth,” the acronym for their fans) who have always supported them. A group of fans from around the world was included in the last part of the concert via video, so BTS could see some faces of their ARMY. During this finale, other fans were projected onto floating cubes, adding to the idea that BTS and ARMY form their own mini universe.

As RM said in his ending statement, “BTS is not just a story of seven people. It’s a story of you, me, and everyone.” BTS’s MOTS ON:E virtual concert emphasized togetherness, regardless of being separated by time and screens. With its innovative use of technology to enhance the group’s dynamic performances, BTS and their fans created new connections through this event, even in a world divided by COVID-19.

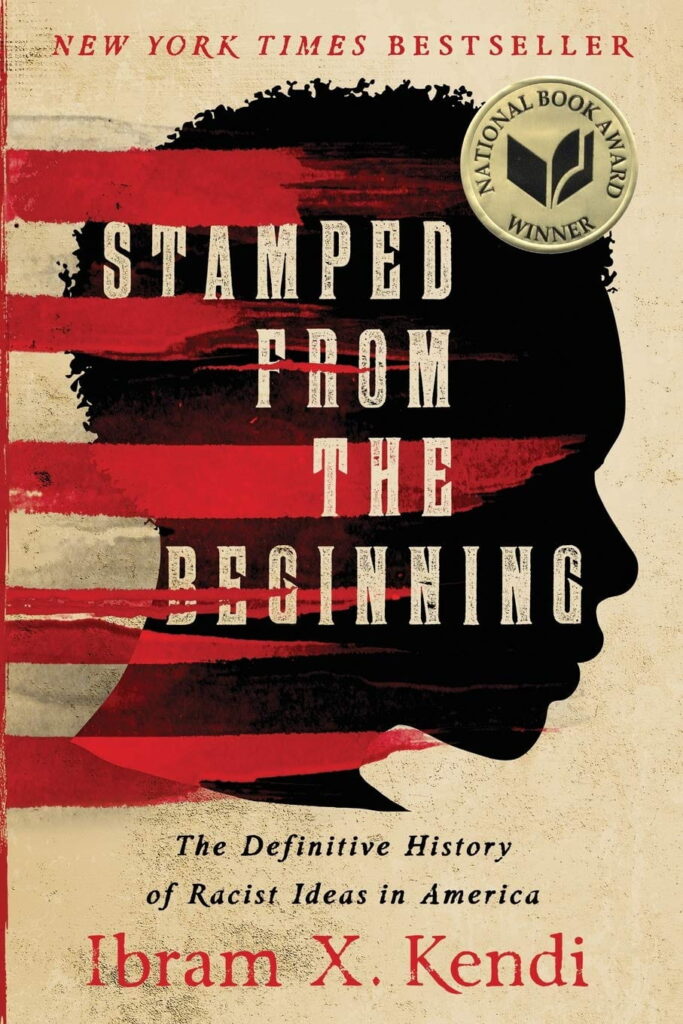

A Must-Read: Stamped From the Beginning

by The Cowl Editor on September 3, 2020

Arts & Entertainment

Ibram Kendi Unturns the Ugly Stones of Racist Ideas in America

by Sara Conway ’21 A&E Co-Editor

“To the lives they said don’t matter.”

With these seven words serving as the dedication, Dr. Ibram X. Kendi opens Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America in remembrance and defiance. This fragment lingers in the readers’ minds as they turn the page to start reading.

Originally published in 2016, the work of the former professor of history and international relations at American University, current director of the Center for Antiracist Research at Boston University, as well as the founding director of the Antiracist Research and Policy Center at American University, received numerous accolades when it was first released. One of these awards included the 2016 National Book Award for Nonfiction.

Stamped From the Beginning jumped onto the New York Times’ bestseller list the week of George Floyd’s murder as the Black Lives Matter movement simultaneously experienced a revitalization in the mainstream consciousness. For those determined to commit to meaningful anti-racist action, but are also uncertain where to begin, Stamped From the Beginning may be a good place to start. Kendi’s book sheds light on a critical part of American history that is rarely taught in schools or discussed in everyday life.

Kendi tracks down the first anti-Black racist idea that then sailed over to the Americas through the Puritans and other pilgrims. He defines a racist idea to be “any concept that regards one racial group as inferior or superior to another racial group in any way” in the prologue (5). Kendi tracks the dominant racist ideas generated during a specific period in American history through five guides, who are notable figures from that time. The book is divided into five sections, titled for the “characters,” as Kendi calls them, of that era. These “characters”—Cotton Mather, Thomas Jefferson, William Lloyd Garrison, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Angela Davis—allow readers to have a main focus, otherwise, the weight and sheer amount of information becomes almost too overwhelming.

This organization is not the only thing that makes Stamped From the Beginning more accessible to the ordinary reader. Kendi writes with an engaging voice that draws readers into a conversation. While the book can be intimidating length-wise as it is over 500 pages, it is available for the general public to read, not just historians. Otherwise, what is the point of writing a book like Stamped From the Beginning if the masses do not read it?

Through this book, readers witness the endless battle between antiracists and the two parties of racist ideas: assimilationists and segregationists. Assimilationists blame racial discrimination and Black people for the “racial disparities,” while segregationists blame Black people (2).

The heart of Stamped From the Beginning, however, proves that it is not hate and ignorance building the racist ideas and forming the racist policies that have continuously existed. Instead, it is the reverse. As Kendi writes, point blank, “Racist policies have driven the history of racist ideas in America.” Racist ideas are conjured to justify these policies and racial discrimination. This then sows hate and ignorance. Readers consistently witness the defiance of logic as racist ideas are written and rewritten to uphold these policies.

Racism does not exist in one form, as Kendi also notes throughout the book. Racism can also be intersectional. There is structural, historical, sexual, medical, class, queer, gender, ethnic, cultural, and political racism. Understanding that racism is intersectional can then alert readers to be aware of where racism exists, to see how deeply ingrained it is in American society, and to, hopefully, change.

With Stamped From the Beginning comes the desire to see more specific studies on racist ideas in the United States, since it is incredibly difficult to fit the details into this book while maintaining the tone necessary for an overview. There is so much to be written about and to be discovered. Hopefully, Kendi’s work is also a definitive call to action for each reader to delve into their own research, starting with what Stamped presents.

The 500-plus-page book may seem daunting to confront, but it is a comprehensible treasure trove of necessary information for Americans, especially. However, Stamped From the Beginning is also a must-read for everyone, as racism exists everywhere.

Kendi’s work was recently adapted into a young reader’s version with the assistance of Jason Reynolds, an award-winning children’s author. Published through Little, Brown for Young Readers this past March, Stamped From the Beginning received a new title as well—Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You. This adaptation carries on Kendi’s goal of making his research accessible, since it can reach an even larger audience, both younger and older.

Stamped From the Beginning is yet again another reminder that racism needs to be acknowledged, conversations that will be uncomfortable must be had, and systems must be overturned. It is time to be aware of our racist histories. It is time to remove these racist policies and ideas that have become an integral part of American society. The time is now.

Seventeen Showcases Versatility on ‘Ode To You’ Tour

by The Cowl Editor on January 30, 2020

Music

Unique K-pop Group Rocks Prudential Center in Newark

by Sara Conway ’21 A&E Co-Editor

If you are somewhat familiar with the K-pop group Seventeen, chances are the first things you think of are their complex choreographies and that they do not, in fact, have seventeen members. The thirteen that make up Seventeen debuted on May 26, 2015 under the South Korean entertainment company Pledis Entertainment with the song “Adore U.”

A unique aspect of the group’s concept was that the members—whose ages range from 20 to 24 years—divide into three sub-units: the Hip Hop Unit (for the rappers), the Vocal Unit, and the Performance Unit (for the dancers). The Hip Hop Unit is composed of the main rappers, S.Coups—who is both Seventeen’s leader and the unit’s leader, although he was absent on the group’s recently concluded North American tour to focus on his mental health—Wonwoo, Mingyu, and Vernon. Woozi, the composer of the majority of Seventeen’s songs, heads the Vocal Unit which also includes members Yoon Jeonghan, Joshua, and vocal powerhouses DK and Seungkwan. Twenty-three-year-old Hoshi takes the role of leading the Performance Unit and creating some of the group’s choreography alongside Wen Junhui, The8, and Dino, the youngest member.

Seventeen, known as “self-producing idols,” embarked on the North American leg of their Ode To You World Tour on Jan. 10, their first stop being the Prudential Center in Newark, NJ. The group’s last world tour in 2017 followed the release of their full-length album TEEN, AGE and landed in venues such as New York’s Terminal 5.

Seventeen’s Ode To You World Tour was announced on the heels of the release of An Ode in September, their longest musical project since TEEN, AGE. The remainder of January saw performances in arena venues in Chicago, Dallas, Houston, Mexico City, Los Angeles, San Jose, and Seattle. The Ode To You Tour will pick up again in March—after the group takes a break in February—continuing their world tour with shows spanning across Europe.

During their concert in Newark, Seventeen showcased their playful and highly sophisticated sides, their growth as artists, and their dynamic as a group. Before the show, member Hoshi secretly joined the random dance play happening outside of the Prudential Center, initially pretending to be a cameraman in the crowd that had gathered. Seventeen kicked off their concert with “Getting Closer,” a song of vocal intensity and incredibly in-sync choreography, automatically setting the tone with lyrics such as, “This dance, you’re getting closer / Breathlessly I want you / Want you.”

The set of Ode To You mixed old, new, fan favorite, and never performed live songs all with the theme of being an “ode to you”— “you” being their fans, named Carats. Hoshi, who acted as the leader in S.Coups’ absence, made a nod to this in his opening statement, concluding with “let’s make a lot of good memories together.”

Following group performances for “Rock,” “Clap,” Thanks,” and “Don’t Wanna Cry,” each unit showed off stages for two of their songs. The Hip Hop Unit performed a remix of “Trauma” from TEEN, AGE and “Chilli” from the group’s mini-album You Made My Dawn, which was released in early 2019. “Lilili Yabbay” from TEEN, AGE and “Shhh,” also from You Made My Dawn, by the Performance Unit kept the energy high in the venue. The Vocal Unit created an emotional atmosphere with their performance of “Hug” from the same album and “Don’t Listen in Secret” from Going Seventeen, closing the unit songs.

Singing “Smile Flower” marked the midpoint of the concert, which the members dedicated to Carats, their fans who have been by their side since May 2015. Seventeen (sans S.Coups) spread out along the edge of the extended stage so that a member faced a part of the illuminated audience. Carats even sang a chorus of “Smile Flower,” filling the arena with mutual emotion: “I can smile because we’re together / I can cry because it’s you / So what can’t I do.” The members gazed out into the crowd, singing quietly along, while bathed in purple-colored light, taking it all in.

Seventeen also showed their fun side and their group dynamic during the Ode To You tour. Seungkwan jokingly told Hoshi and Joshua, “It’s not your solo concert!” and to stop hogging the spotlight when the two captured the attention of the audience and the cameras during the opening statements. The members also playfully pushed Wonwoo towards the front of the main stage to demonstrate his “feeling” of being on tour. In response, he screamed, “Make some noise!” (without a microphone) in his deep voice which carried out to everyone in the crowd. During the ending statements, various members, including Hoshi and Jun, did an energy check. Earlier that evening Seungkwan switched the lyrics of the group’s song, “Moonwalker,” for “Newarker.” Jun brought the pun back by having the crowd sing “moonjunwalker” multiple times.

The fun continued with the stages set in the “SVT Museum.” As the lights came up, the audience found the members frozen in poses behind huge frames as if they were part of an exhibit. The older songs performed with this set—debut song “Adore U,” “Pretty U,” and “Oh My!”—were paired with bright colors, looser costumes, and lighthearted but energetic choreography. However, the synchronization Seventeen is well known for remained even in these playful songs.

To wrap up the “SVT Museum” portion of the concert, all of the members performed “Just Do It,” which is normally a BSS (BooSeokSoon) unit song. This unit was formed in 2018 with the release of the digital single “Just Do It” and comprised vocalist Seungkwan (his last name is Boo), vocalist DK (his real name is Seokmin), and performance leader Hoshi (his real name is Soonyoung). To kick off the song, DK shouted into the crowd, “They call us…Seventeen!” adjusted from “They call us BooSeokSoon!” to fit the all-member version.

Ode To You in Newark closed with the never-ending “Very Nice.” As soon as it seemed like the concert was officially over, there was another upbeat burst of the chorus, “Aju nice!” and another thick flurry of confetti raining over the crowd. The concert was really thought to be over after the third repeat when the members went back to the main stage and took their bows, supposedly concluding with their cheer, “Say the Name, Seventeen!”

Seventeen fooled their fans yet again when the members waved goodbye as the Ode To You divider slid shut. There was a split moment of fans starting to gather their things when the chorus came blasting back. With the new repeat of “Aju nice!” Hoshi raced ahead of the rest to the extended stage among another burst of white confetti. The real end and the last goodbye had officially come: after their bows and their last cheer, Seventeen sang the closing line of the song from their reality television show, “Going Seventeen.”

The first show of the Ode To You world tour in North America was one filled with laughter, fun, and heartfelt emotions between the members of Seventeen and their Carats—the fans who have cheered on the group through their artistic journey, as the lyrics of “Smile Flower” say, “Our smile flowers bloom / I’ll be the spring to your smile.”

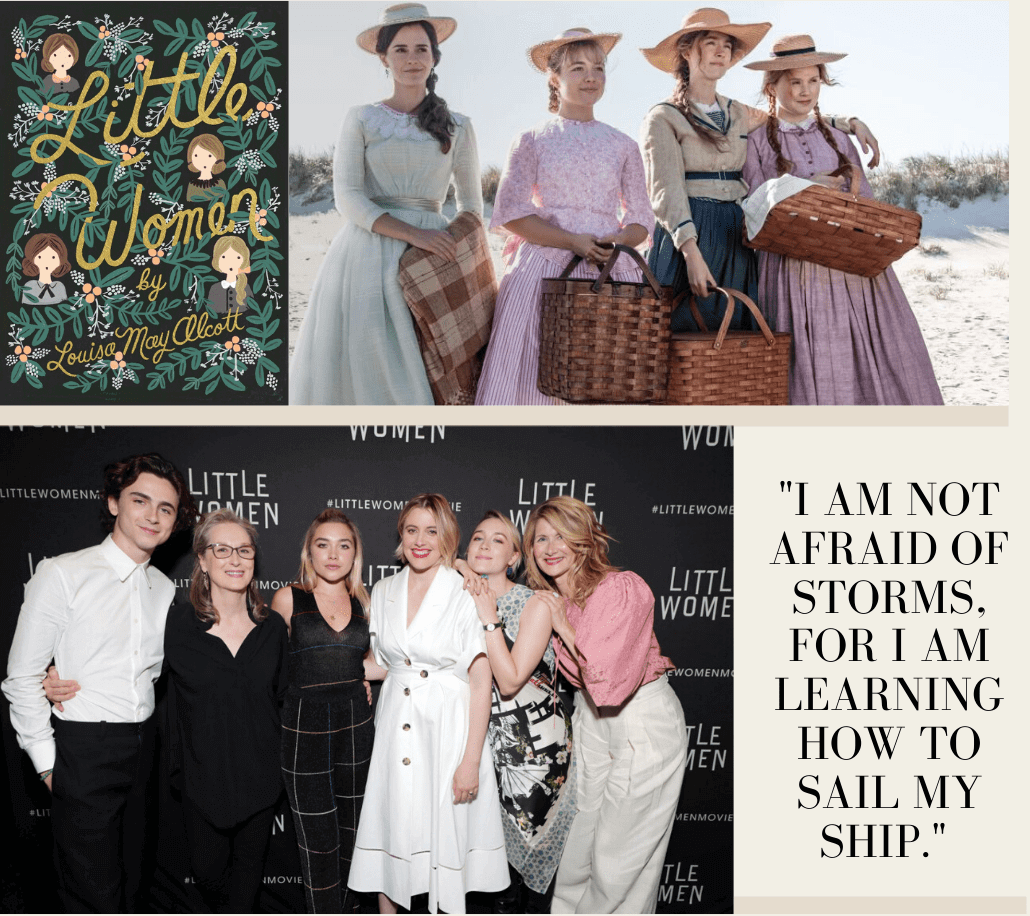

The Artistry of Little Women Tells a Beloved Story

by The Cowl Editor on January 16, 2020

Arts & Entertainment

Director Greta Gerwig Highlights Attention to Detail

by: Sara Conway ’21 A&E Co-Editor

“I like good

strong words

that mean something.”

So says the iconic, empowering, stubborn, and complicated Jo March of the novel Little Women by Louisa May Alcott. The most recent adaptation by director and writer of the screenplay Greta Gerwig—which opened on Dec. 25—however, combines the force of the “strong words” that draw Jo’s attention and the power of unspoken elements to bring new magic to the story.

As the director and writer, Gerwig strays from following the typical narrative structure of Little Women which goes in chronological order in the original classic. She decides to follow a nonlinear narrative to tell the story through the eyes of Jo March as she looks back on her childhood memories while rushing home to a deathly sick sister Beth.

Gerwig drew upon the novel and the writings of Alcott to weave together this version of Little Women where Jo March is the alter ego of Louisa May Alcott, “reflect[ing] back and forth on her fictional life.” The second eldest March girl parallels the life of her creator: the two were writers and each had three sisters. However, while Jo married in the book, Alcott remained single.

By having this doubling of childhood and adulthood narratives, all which are present in the book, Gerwig states that one can “look at how you become who you become, because I always feel like you’re walking with your younger self, and answering to her.” Jo sees her childhood through her lens of adulthood and can understand what brought her to where she is now.

Through this alternation between past and present, viewers see the strict distinction between Jo’s memories of her past and her current reality. The scenes from the March sisters’ childhood are colored with warmth and sunshine, full of love and bursting with exuberant energy.

This warmth is cut by the aesthetic of the present; the filter of cold blues and dark shadows highlight Jo’s growing feeling of emptiness in her life as her family changes. Coldness seems permanent after burying Beth, who perished from complications that arose from a childhood bout of scarlet fever. The warm glow of the sun sets behind the mourners and the trees, an indication that the March sisters’ childhood has truly reached its end.

In an interview with Vanity Fair where some members of the cast and Gerwig broke down a scene from Little Women, Saoirse Ronan, who plays the fiery Jo, points out that the four March girls have their own distinct colors. Gerwig continues the observation by adding that Meg’s color is green, Jo often wears a red cape, and Amy wears mostly blue. In addition, the costumes that Beth tends to wear throughout the film are purple. Marmee’s costumes, Gerwig notes, weaves together all of her “little women’s” colors because she is “all of them in one.” Marmee reflects a unification of her daughters as “different parts of her spirit went into each girl.”

The film’s score, composed by Alexandre Desplat, tells a story of its own while complementing the narrative of the beloved Little Women. Music, in fact, is present in most of the film. Gerwig wanted her adaptation to feel like a “musical without lyrics,” which inspired Desplat to create a score with a “modern sense of urgency” that was “dynamic and intimate.”

To bring Little Women to life through music, Desplat kept his ensemble small: he only used a 40-piece string orchestra with additions from a harp, flute, clarinet, celeste, and vibraphone. The main focus, however, was the centrality of the two pianos, and, thus, two sets hands, which reflected the four March sisters. Through this score, Desplat captured moments and answered the question, “Is [the film] a real story or is it the book [Little Women] being written?” The music responds: the audience is “reading the book with images.”

In an interview with the LA Times, Gerwig contemplates, “What you choose to tell and how you choose to tell it indicates to an audience what’s important.” Gerwig builds a story around deep, resonating emotion—viewers are right there with the characters as the Marches experience love, heartbreak, frustration, joy, and crippling sorrow. Little Women tells its timeless tale through subtle details found in the lighting, color choices, and the score of the film.