Tag: William Burleigh ’19

Childish Gambino’s Final Tour: This Is America: Donald Glover to Drop Rap Alias After Completion of Next Album

by Kerry Torpey on September 20, 2018

Arts & Entertainment

by William Burleigh ’19

A&E Staff

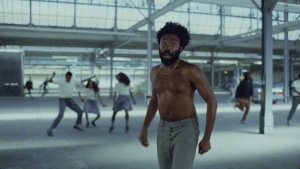

On Sept. 6, Childish Gambino kicked off his This Is America tour in Atlanta, Georgia. The rapper, whose real name is Donald Glover, confirmed at the concert that this will be his last tour under the Childish Gambino name: “If you’re at this show, then you know that this is the last Gambino tour ever.”

Glover had previously hinted at a retirement of the Childish Gambino moniker in January when he said that the next album he releases under the name will be the last: “I stand by that,” he said of the retirement claim. “I’m really appreciative of this. I’m making another project right now,” he said. “But I like endings, I think they’re important to progress,” he continued. “I think endings are good because they force things to get better.”

Fans of Glover should not despair, for, the wording of his statement, “the last Gambino tour,” does not necessarily rule out future albums or live performances under a different name. In fact, many of his fans firmly believe that his final Gambino album will not be the last album Glover ever releases, due to the constant growth of his musical style and rising celebrity status.

At his show in Boston on Sept. 12, Gambino gave a fantastic performance. After opening by informing the audience, “This is not a concert. This is church,” he rapped popular hits such as “I. The Worst Guys,” “II. Worldstar,” and “V. 3005,” off his 2013 album Because The Internet. He interspersed these with more soulful funk songs such as “Boogieman,” “Riot,” and “Terrified,” from his 2016 album Awaken, My Love! along with his recent hit single “Feels Like Summer.”

He closed his setlist with a fiery performance of his 2018 song “This Is America,” which took the internet by storm in May, en-route to becoming Gambino’s first no. 1 single. During this song and throughout his Boston show, Gambino captivated his audience with the eclectic, contortionist dance moves that he popularized in the critically-lauded and much-discussed music video for “This Is America.”

Gambino ended his show’s encore with a soulful rendition of his Grammy Award-winning hit “Redbone.” His voice dripped with emotion as he repeatedly nearly screamed at the audience, imploring them to “Stay woke!” a fittingly dramatic end to an outstanding performance.

Whenever the retirement of the Childish Gambino name does occur, Glover will certainly not be pressed to find work, as he has appeared in a growing number of movie roles recently. Last summer, he appeared in Spider-Man: Homecoming. This past May, he dazzled audiences as young Lando Calrissian in Solo: A Star Wars Story. Next summer, he will voice the role of Simba in the upcoming live-action remake of Disney’s The Lion King.

Glover’s most popular work outside of his music career remains his television show Atlanta, which he writes (along with his brother Stephen), directs, and stars in. Atlanta, which portrays two cousins navigating the rap scene in the titular city, has received immense critical acclaim and various accolades, including two Golden Globes and six Emmys. Atlanta has been renewed for a third season, which will premiere in 2019.

Glover’s This Is America tour will hit 18 locations across the United States (and one show in Vancouver) and conclude in mid-October. His upcoming album, the fourth and final as Childish Gambino, is currently untitled and does not have a set release date, although it is expected at some point in late 2018.

BlacKkKlansman Sparks Hollywood Debate

by The Cowl Editor on September 13, 2018

Arts & Entertainment

Spike Lee and Boots Riley Disagree on How To Portray the Police in Film

by: William Burleigh ’19 A&E Staff

This summer, director Spike Lee released his newest film, BlacKkKlansman. Based on true events adapted from Ron Stallworth’s 2014 memoir Black Klansman, it had previously premiered at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival in May, where it won the Grand Prix award.

Set in the 1970s, BlacKkKlansman tells the story of Stallworth (John David Washington), the first African American detective in the Colorado Springs Police Department, as he sets out to infiltrate and expose the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. Stallworth accomplishes this by communicating with the leader of the KKK, David Duke (Topher Grace), over the phone and pretending to be white. The police then send a white officer (Adam Driver), posing as Stallworth, to insert himself into the chapter.

BlacKkKlansman received acclaim from critics, especially for its timely themes of race relations in America. It also performed well at the box office, with a current profit of $66.3 million (as of now), which is Spike Lee’s best since 2006.

But it has not gone without criticism. On Aug. 17, Boots Riley—another African American director—took to Twitter to voice his criticism of BlacKkKlansman with a three-page essay. Riley also released a film this summer.

In July, his absurdist dark comedy Sorry to Bother You received universal acclaim from critics, who praised Riley’s original, innovative script and direction. The film, set in Oakland, California, tells the story of a black telemarketer who puts on a “white voice” to become more successful in his career.

Interestingly, the plots of Sorry to Bother You and BlacKkKlansman revolve around a black character both pretending to be white over the telephone to achieve their goals. Riley has stated that this coincidence has nothing to do with his criticism of Lee’s film or the timing of their respective release dates.

Riley opened his essay by stating that it serves “not as much an aesthetic critique of the masterful craftwork of this film as it is a political critique of the content and timing of the film.” He also stated that he considers Lee to be a “huge influence” on his own career and a person whom he holds in the “highest respect as a filmmaker.”

Riley’s criticism voiced his disappointment with Lee’s portrayal of the Colorado Springs police in a positive light. He deems this portrayal harmful in light of the Black Lives Matter movement and the ongoing issue of police brutality towards the African American community.

Riley states that he takes issue with the fictional elements of BlacKkKlansman that he believes were “made up for the movie to make the police seem like heroes.” These plot points were “put in the movie to make Ron and the rest of the police look like they were interested in fighting racism, like they don’t all protect whatever racist and abusive cops are in there,” said Riley.

Riley reveals that the real Stallworth was actually a part of the FBI Counter Intelligence Program (Cointelpro) and “infiltrated a black radical organization for years (not for one event like the movie portrays)” to sabotage it while fighting against racist oppression.

Riley states that he doubts the validity of Stallworth’s memoir and believes that the events it depicts were embellished by Stallworth to “put himself in a different light.” He also points out that the memoir was “published by a publisher whom specializes in books written by cops.”

Riley summarizes his criticism of BlacKkKlansman towards the end of his essay: “[T]o the extent that people of color deal with actual physical attacks and terrorizing due to racism and racist doctrines—we deal with it mostly from the police on a day to day basis. And not just from white cops. From black cops too. So for Spike to come out with a movie where story points are fabricated in order to make a black cop and his counterparts look like allies in the fight against racism is really disappointing, to put it very mildly.”

On Aug. 24, Lee responded to Riley’s critiques in an interview with the UK publication The Times. When asked about Riley’s essay, Lee responded, “Look at my films: they’ve been very critical of the police, but on the other hand I’m never going to say all police are corrupt, that all police hate people of color. I’m not going to say that. I mean, we need police.” He would continue to acknowledge that, “Unfortunately, police in a lot of instances have not upheld the law; they have broken the law.”

Lee goes on to imply that he values the dialogue that Riley has contributed to about diversity of opinion in the African American community, “But I’d also like to say, sir, that black people are not a monolithic group. I have had black people say, ‘How can a bourgeois person like Spike Lee do Malcolm X?’”

Ultimately, while Lee and Riley disagree about the ways that they tell stories about the struggles of black men and women in America, their respective works BlacKkKlansman and Sorry to Bother You are both excellent, important films worth seeing.

Academy Awards Introduces Best Popular Film Category

by The Cowl Editor on August 30, 2018

Arts & Entertainment

by William Burleigh ’19

A&E Staff

Recently, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced the addition of a new competitive category at the Oscars to recognize the “best achievement in popular film.” This new award is set to debut at the 91st Academy Awards in February 2019. It is the first new category at the Oscars since 2002, when the Academy introduced the award for Best Animated Feature.

While they have not released any information regarding specific details about the new category, it seems to be tailored to big summer blockbusters and superhero films; films that are traditionally overlooked for the more prestigious awards of Best Picture and Best Director in favor of more technical categories, such as Sound and Visual Effects.

Several critics have compared this exclusion of popular films from prestigious categories—and the subsequent creation of a category catered to them specifically—to the backlash that the Academy faced in 2008 when critically acclaimed blockbusters The Dark Knight and WALL-E were not nominated for Best Picture. This led to the expansion of the Best Picture category from five nominees up to 10. Most years since have seen nine films nominated.

The announcement of the category, Best Popular Film, has been met with a nearly universal negative response. Many view it as a desperate attempt to cater to mainstream audiences, in hopes of increasing annual ratings since the 90th Oscars hit an all-time low this past March. Others have criticized the award for diminishing the reputation of the Oscar brand, which is historically meant to be prestigious and desirable.

Some view the decision to add a popular film category as a way for the Academy to acknowledge blockbuster movies and studio tentpoles that often do not make the cut for Best Picture. This creates issues stemming from the fact that putting studio blockbusters in a “popular” category suggests that they usually are not as artistic as the indie movies that get nominated for Best Picture.

With this announcement coming ahead of an awards season where Black Panther is considered by many to be a major contender for Best Picture, the Academy is facing even more criticism. Black Panther has received enormous critical acclaim in addition to breaking numerous box-office records since its February release. On Aug. 5, it became the third film to ever gross $700 million domestically, after Avatar and Star Wars: The Force Awakens.

Black Panther, viewed by many as being transcendent of the superhero genre due to its cultural significance and strong African American representation, was widely predicted and even assumed to become the first superhero movie to be nominated for the Best Picture category. With the creation of the Best Popular Film category, these chances could be diminished; critics are worried relegating Black Panther to a popular film category will hurt its chances of being nominated in the more prestigious ones.

The Academy has since released a follow-up statement in response to this backlash ensuring that any single film is eligible to be considered for both the Best Picture and Best Popular Film categories. However, many remain unconvinced that the Oscars will not be relegating blockbusters worthy of an award—such as The Dark Knight, Inception, Mad Max: Fury Road, La La Land, Get Out, Wonder Woman, and Black Panther—to a “consolation prize” of Best Popular Film instead of allowing them to compete in prestigious categories and earn meaningful awards.

Only when the Academy announces the eligibility rules for the Best Popular Film category at a later date will the public find out how the Oscars define “popular,” and whether they intend to judge films based on genre or content.

Students Confront Social Issues: Providence College Holds Ninth Annual Celebration of Student Scholarship and Creativity

by Kerry Torpey on May 3, 2018

Arts & Entertainment

by William Burleigh ’19

A&E Staff

Last Wednesday, Providence College held its ninth annual Celebration of Student Scholarship and Creativity. The event showcased the scholarly, creative, and service work that PC students have accomplished this year on campus, in the community, and around the world. Students from all class years, majors, and disciplines presented their independent studies and passion projects with poster boards and other media displays in the Slavin Center.

Maalik Mbatch ’18, a studio art major, showcased his photography project focused on digital imaging. The goal of Mbatch’s work, completed over the span of seven months, was to explore the psychological relationship between memory and childhood trauma. He showcased two photographs, from his larger presentation that was displayed in the Smith Center for the Arts earlier this semester.

His unique photos displayed basic scenes from his childhood, with a touch of intrigue. Mbatch utilized Photoshop to blur and distort the facial features of himself and his family members in the photos. This is meant to symbolize how memories of scenes can be distorted and changed depending on our emotional feelings towards the events.

Mbatch described how his project was cathartic for him because it allowed him to confront traumatic events from his childhood. He also stressed the importance of self-actualization as a senior approaching graduation, saying, “My project taught me how to address trauma and mental health in a healthy way. It also helped me to work with the events of my past, as opposed to allowing them to become suppressed. I feel it’s important as a college graduate to acknowledge what kind of person I was and what kind of person I’m going to be.”

Sophia Forneris ’18, another studio art major, presented her photography project confronting and examining the emotional effects of sexual assault. Forneris, who has been working on her project for two years, sought to use her photographs to represent the feelings of loneliness that women experience while dealing with the effects of sexual harassment and assault. Forneris displayed three black-and-white photographs—also part of a larger collection previously shown in the Smith Center—of women alone in intimate, yet isolated situations.

She paired these with a booklet containing a compilation of text messages that female PC students received from males looking to initiate sexual encounters. The texts, and other social media interactions, were all intended to be incredibly graphic and distasteful. Forneris collected these texts from girls around campus to highlight how disturbingly aggressive some males can be in daily online interactions.

Forneris hopes that her project can bring awareness to the ongoing issues of sexual harassment and assault and its effects on women. She said, “I feel like as a community, it is a subject we have discussed this year with the #MeToo Movement. But I want us as a community to understand that we have the duty to create functioning individuals that will succeed after college.”

Manya Glassman ’19, a film minor, presented her nine-minute short film entitled A Stay in Japan. Manya shot the short film in the spring of 2017, when she attended PC’s Maymester in Japan. A Stay in Japan tells the story of a shallow American model who travels to Japan and has an unexpectedly eye-opening experience.

Glassman sought to explore themes of values, enlightenment, and transformation with her work. She hopes that her short film can bring a higher level of insight and cultural awareness to Americans.

Glassman said, “I wanted this film to encapsulate how occupied we’ve become with our own lives and our own culture. We’ve been raised in our American way in our American culture. We always think we’re right. And we need a more global perspective. Living in America, I don’t think we try to explore other cultures as much as we should. With this film, I tried to show how sometimes we are so caught up in our own lives and culture that we don’t take the time to stop for a moment and appreciate other communities.”

PC Celebrates “Black Women in Film”

by Kerry Torpey on April 26, 2018

Arts & Entertainment

by William Burleigh ’19

A&E Staff

Providence College’s Department of Black Studies recently completed a series of weekly film screenings titled “Black Women in Film.” The goal of the series was to celebrate films directed by African American women, an often underrepresented, underappreciated group in mainstream cinema. The third and final screening of the series was Pariah (2011), written and directed by Dee Rees.

Pariah tells the story of Alike, a young African American girl struggling to come to terms with and embrace her identity as a lesbian. Much of the conflict in this powerful story revolves around Alike’s relationship with her conservative parents and their attempts to suppress her sexual orientation. As Rees’ feature film directorial debut, Pariah originally premiered at the 2011 Sundance Film Festival and was awarded the Excellence in Cinematography Award.

The “Black Women in Film” series previously screened Dee Rees’most recent film, Mudbound (2017), which she also wrote and directed. Mudbound, a historical period drama, tells the story of two post-World War II families—one black, one white—their relationship with one another, and racism in rural Mississippi. Mudbound was praised by critics and Rees’ script was nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay at the 2018 Academy Awards.

Mudbound’s promotion of black women in film stretched beyond the directorial position. Rachel Morrison, the director of photography, was nominated for Best Cinematography at the Oscars. Morrison became the first ever woman to be nominated in the category. Additionally, well-known actress/musician Mary J. Blige became the first African-American woman to receive multiple Oscar nominations in the same year, with nods for Best Supporting Actress and Best Original Song.

Another black woman making significant strides for African-American representation in film is writer and director Ava DuVernay. Her breakout film Selma (2014), a Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. biopic, was nominated for Best Picture at the 2015 Academy Awards, making DuVernay the first black female director to have her film nominated for Best Picture.

DuVernay’s historical documentary 13th (2016)—named after the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which outlawed slavery—explores issues of racial injustice present in the American prison system, specifically the mass incarceration of African American men.

13th went on to be nominated for Best Documentary Feature at the 2017 Academy Awards, making DuVernay the first black woman to be nominated by the Academy in the Best Director category.

DuVernay’s recent fantasy film A Wrinkle in Time—a Disney adaptation of the 1962 novel by the same name—was released in March of this year. Featuring Oprah Winfrey, Mindy Kaling, and Reese Witherspoon, A Wrinkle in Time was celebrated for its message of female empowerment and diversity. DuVernay became the first woman of color to direct a live-action film with a budget of over $100 million, and the third woman to do so after Kathryn Bigelow (K-19: The Widowmaker, 2002) and Patty Jenkins (Wonder Woman, 2017).

DuVernay will be continuing her hot streak with another blockbuster, having recently been hired by Warner Bros. and DC Comics to direct a big-budget adaptation of The New Gods, a comic-book series from the 1970s.

Ultimately, the works of Rees and DuVernay serve as testaments to the abilities of African American women to create meaningful, entertaining, and important films when granted the opportunity. Many are hopeful that Hollywood studios will take notice of their success and offer a greater amount of directorial opportunities for not only African American women, but all women of color.

What Makes Black Panther, Black Panther

by Kerry Torpey on April 19, 2018

Arts & Entertainment

by William Burleigh ’19

A&E Staff

T’Challa is still king. Black Panther has officially surpassed Titanic in the domestic box office. On Saturday, April 7, Black Panther outdid the 1999 epic’s $659 million when it reached $665 million. It is now the third highest-grossing film in North American box office history (not adjusting for inflation). It ranks number three behind 2015’s Star Wars: The Force Awakens’ $936 million and 2009’s Avatar’s $760 million.

Black Panther, the 18th film in the Marvel Cinematic Universe superhero franchise, has taken the box office by storm since its Feb. 16 release, breaking numerous records: it is currently the highest-grossing film of 2018, raking in over $1.3 billion worldwide. Black Panther has also become the highest-grossing superhero movie of all time, passing The Dark Knight and Marvel’s own The Avengers.

Black Panther features almost an entirely black cast, starring Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong’o, and many more. Black Panther has been praised for its diversity not only onscreen but also behind the camera. Young African-American director Ryan Coogler had only ever made two other feature films and now holds the records for biggest box office debut for an African-American director and highest grossing film by and African-American director.

The film’s success and relevance extends far beyond its box office domination. The film also received universal critical acclaim and rave reviews—and not just for being an entertaining action movie. Since its release, Black Panther has been lauded by the black community for its cultural significance, and specifically, its emphasis on and commitment to underrepresented voices in a Hollywood blockbuster. This is an increasingly important task for mainstream films, as black audiences have been massively marginalized in the history of cinema.

One reason the film has been so vastly successful is because it offered black audiences a cinematic experience they have been sorely missing: a black superhero. White audiences have enjoyed nothing short of a plethora of superheroes to choose from: Iron Man, Batman, Superman, Captain America, Spider-Man and Thor alone have made a combined 35 appearances in major superhero movies since 2002. In this way, black audiences who sought inspiration and entertainment from a superhero who looked like them have been left underwhelmed for many years.

The need for representation obviously transcends the superhero genre. The history of film as a whole has been dominantly populated by white voices. The most iconic characters of all time—James Bond, Indiana Jones, Luke Skywalker—are all white. If you Google-search “best actors of all time,” the automatic top 50 listed results display only four people of color. Searching results for “best directors of all time” displays only two people of color in its top 50. Some of the greatest movies—The Godfather, Casablanca, It’s A Wonderful Life, Fight Club, and The Lord of the Rings—feature no black characters and require African-American audiences to view their stories through the eyes of white characters.

And yet Black Panther has still made more money than all of them in just eight weeks. Now more than ever, black audiences are finding themselves represented in mainstream films. Two years ago, Moonlight (2016) won the Academy Award for Best Picture. Last year, Get Out (2017) made $176 million and won Best Original Screenplay. This year, director Christopher Nolan, The Dark Knight trilogy, Inception, has predicted that Black Panther will become the first ever superhero movie to be nominated for Best Picture.

Ultimately, Black Panther and its box office records serve as a testament to the strength of diverse voices and the increasing need for more representation in Hollywood films of all genres and budgets. Black Panther will of course be remembered as an entertaining movie. But, more importantly, Black Panther’s cultural relevance, as both the first mainstream black superhero movie and a major blockbuster will resonate universally with audiences of different backgrounds as a source of hope, affirmation, and inspiration.